Pictured: Captain Richard Balfe.

(Courtesy of Dorothy Deegan)

The events that took place in Dublin at Easter 1916 has since left the city with whispers of heroic ghosts and the Dublin 4 area has a dense concentration of tales that have been preserved intact through generations of oral history.

The star of this particular story, however, lived until 1997, with his quietly held convictions close to his chest and his remarkable bio only coming to light through his grand nephew, Derek Murphy.

Captain Richard Balfe, from 13 Pembroke Street, Irishtown, played an active role in the armed rebellion, taking his orders directly from Seán Heuston himself. His witness statement reveals his direct contact with the big names of the rising, recounts the injuries and deaths of those close by, and describes how he himself narrowly escaped death but lived to pass on this story.

Richard Balfe, known locally as Dick, started on his path in 1911 when he became a member of the Meirleaca Club, a revolutionary club in Ringsend, and progressed to the Fianna, where he trained under Father Flanagan, who was subsequently arrested for his role in revolutionary activity.

In 1913 he was sworn into the IRB and joined the Volunteers, taking part in the Howth gun running of July 1914. According to his statement, the ‘split’ left only 11 from a battalion of 800, which formed the D company that trained at the seafront at Sandymount. That company was regarded as the scouts of the 1st Battalion, always heading marches and took part in the flying column to Rathdrum at Easter 1915.

As well as being responsible for the training of the company his home in Irishtown was used as a arms dump for the receipt of Mauser rifles.

This information is contained in the witness statement obtained from him by the Bureau of Military History. The BMH Collection, 1913-1921, is a collection of 1,773 witness statements; 334 sets of contemporary documents; 42 sets of photographs and 13 voice recordings that were collected by the State between 1947 and 1957, in order to gather primary source material for the revolutionary period in Ireland from 1913 to 1921.

In his statement, he goes on to outline what he experienced on Easter week 1916. “On the Good Friday previous to the Rising I was sent for and we prepped in Blackhall St. We got the mobilisation order on Monday and I went to Liberty Hall. Madame Markievicz was going around with drinks. I got my orders at about 11.25am. It was headed ‘The Army of the Irish Republic’ and signed by Connolly. I was to take the General Post Office by the side door. At [11.40] Connolly told me that the person assigned to take the Mendicity Institute had failed and I was to proceed there immediately and hold at all costs to prevent troops from passing to the city from the Royal Barracks.”

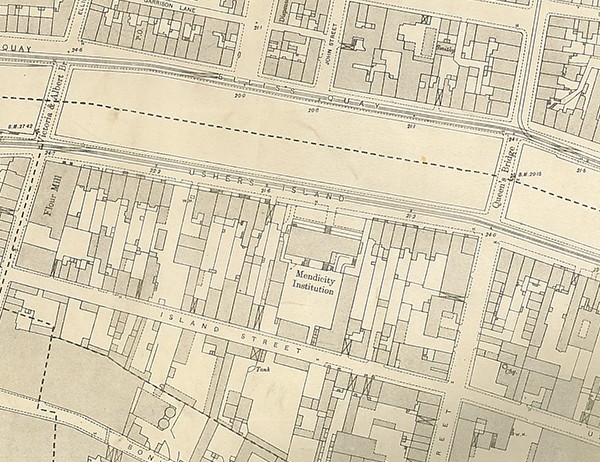

The Mendicity Institute, which is on Usher’s Island, (see accompanying map of the area dating from 1909) was a strategic stronghold particularly during the opening hours of the conflict. Initially, they were only supposed to hold this building for two hours. The two-storey building provided a bird’s eye view of the troops advancing towards the city from across the River Liffey. It is possible that this is where the British suffered one of their first casualties, Lieutenant Gerald Aloysius Neilan of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Pictured Above: Mendicity Institute map.

Balfe continues in his statement. “On the stroke of 12 o’clock a small party of Sappers came unarmed which we allowed to pass. All sixteen of us had Lee Enfield rifles and at least 100 rounds of ammunition. Two shots were fired and the Commanding Officer dropped. It was a case of fire and one could not miss. Eventually, the British soldiers ran up the side streets. At 4 o’clock they came down eight deep and we altered our tactics and concentrated on the rear of the column. Then we suddenly concentrated on the head of the column and no man got past Queen St Bridge.”

That was the end of the first day. Already they had surpassed all expectation and Connolly sent a message of congratulations from the GPO; but no further instruction.

The following day saw the British taking up positions from Benburb Lane. Then what followed from the Royal Barracks was one of the most famous bayonet charges, according to Balfe. His statement continues, “The charge had flags, fixed bayonets and swords. We continued with the same tactics, concentrating on the rear of the column. They went up Queen Street but were attacked by our troops and did very little damage to us.

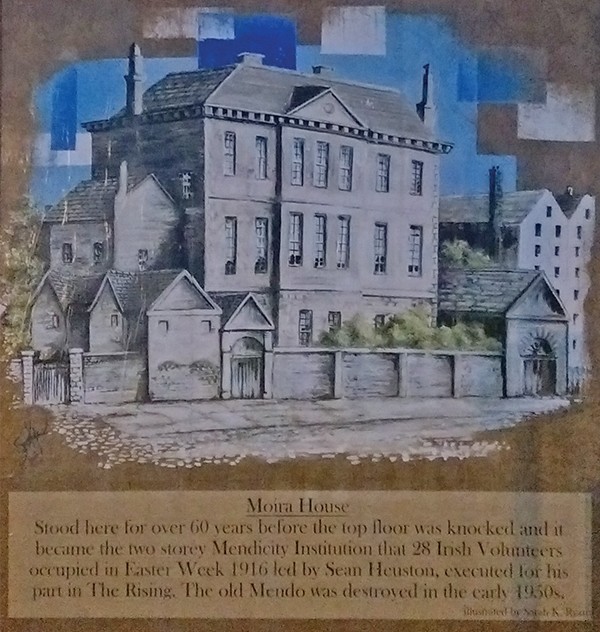

Pictured Above: Mural on wall of Mendicity Institute where Balfe fought.

(Images courtesy of 1916 Mendicity Garrison relatives)

“On Wednesday it opened up with machine gun fire and we were completely surrounded. No word of retreat came and our ammunition and supplies were now exhausted. Willie Staines and myself were wounded by a bomb. Heuston bandaged Staines, ordered the surrender and put out a white flag. I was left behind, thought to be dead. Late in the evening I heard the British breaking in. While a British Officer and Dublin Fusilier were deciding whether to use a bayonet or a bullet on me, an officer of the RAMC came in and claimed me as his prisoner saying there had been, ‘enough of this dirty work.’ I was removed to Richmond Barracks, Wakefield and later to Frongoch. Every man in the Mendicity was tried and sentenced to death.”

Derek Murphy who brought this priceless document to light in time for the centenary of the Rising is currently exploring the possibility of having a commemorative plaque erected in honour of his remarkable grand-uncle.

By Maria Shields O’Kelly