Above: The legendary Micko O’Neill with daughter Mary and her partner John (Scotchie) Byrne.

Michael O’Neill, or “Micko” as he has always been known, was born on February 24, 1921.

Beyond the walls of 5 Fitzwilliam Street, his first home, the Irish War of Independence was raging. Later that year, the historic Anglo-Irish Treaty (December 1921) was signed, leading to the establishment of the Irish Free State.

Despite the fact that the newly-formed State struggled with huge social and economic problems, the Ringsend of Micko’s childhood was “a great place to grow up”.

He went to Ringsend Boys National School. At least he did some of the time, although he would go on the hop with his friends whenever they got a chance, hiding their schoolbags in Ringsend Park and making their way to the banks of the Dodder or the Liffey, playgrounds that provided plenty of opportunities for mischief and fun.

They made sure to keep clear of Mrs. Barry, who also lived on Fitzwilliam Street, because she would throw cold water down on their heads from an upstairs window if she spotted them on the move.

Micko was only thirteen when he left school but that was the norm back then. He went to work as a delivery boy for Clyne’s Butchers, three days a week, earning half-a-crown a day. Five shillings of that would go to his mother for his upkeep and the rest he would spend on his greatest passion, “going to the pictures.”

He loved “the pictures,” especially cowboy films. Every week, he would go to the Regal or the Palace to see the latest releases. He was mesmerized by the glamorous looks and colourful lives of the actors and actresses he saw on the big screen, so very different to life in Dublin, and took great delight in star spotting.

He saw many of his favourites when they came to town to promote their work or to holiday. In his day he has seen some of the greatest stars in the world, including John Wayne, James Cagney, James Stewart, Cassius Clay, JFK, Kim Novak, Bing Crosby and Grace Kelly. One of the highlights of his life was seeing Judy Garland perform at the Theatre Royal, Dublin, in 1951.

It was the glamour of the smart red uniform that led him to announce his plan to join the Irish Guards when he was about fourteen, before the last war. His father, a coalman, put his foot down and told him in no uncertain terms that no son of his would be joining the British Army.

Micko joined the Irish Army instead and spent five of the happiest years of his life as a gunner. He was proud to serve under Eamon De Valera, his Commander in Chief, who he describes as the “most brilliant statesman in the world.”

After a spell as a docker “which was very hard work” he ended up in the Irish Glass Bottle factory as a shift worker and stayed there for 35 years until his retirement.

In 1954 he married Eileen, also known as Nelly, who shared his love of dancing, theatre and film. They had permanent seats at the Theatre Royal and saw almost every show that the theatre put on. Their only child, Mary, still lives in the family home in Ringsend.

A lifelong member of St Patrick’s Rowing Club and a passionate supporter of Shamrock Rovers since childhood, Micko is a fount of knowledge when it comes to sport and remembers sporting fixtures with perfect recall. He could give Giles and Dunphy a run for their money any day as a pundit.

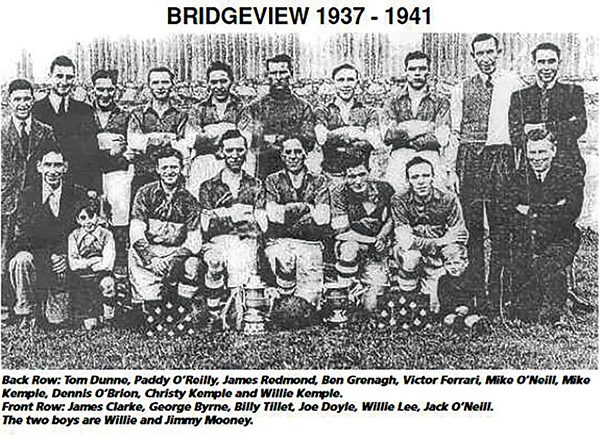

Pictured: Bridgeview FC.

He always supported local or Irish International teams and has scant interest in British football. One of his all-time favourite teams was Bridge View, a football team based in Ringsend (1937-1941). He told NewsFour that when he was in the army he would rush to buy the paper every Friday to see how they were doing. Bob Fullam, a Ringsend man who played for Rovers, and for the Irish team, was a particular sporting hero. Micko himself played in goal for Derry Rangers in 1943.

His greatest love is for St Patrick’s Rowing Club, where he is a legend amongst the members. He recalls with great pleasure their first regatta in 1936, which they won. The names of the winning crew come easily to him: Mulder McDonald, Saul Cox, Dinnie Doyle and Francis Murphy.

Micko now lives in the Ailesbury Nursing Home in Sandymount, where his wicked sense of humour, his glorious singing and his indomitable spirit mean that he is popular with the other residents and with the staff.

Every day he reads the newspaper, cover to cover, and is very well informed, with strong opinions about what is going on in the world. For example, he hates the new incinerator in Dublin Bay and told NewsFour: “You won’t be able to cross the road when that thing opens. I’d love to call the IRA and get them to put a bomb under it.”

It’s not just crossing the road he’s worried about; he makes the point that the operators, Covanta, have had emission problems with similar incinerators elsewhere.

In spite of all the problems in the world, Micko declares: “Life is better now, everything is different – people, technology – but life is easier and better today.”

He always loved singing, and still does. His repertoire includes songs from all his favourite singers, including Perry Como, Gene Autry, Count John McCormack and Bing Crosby. He is still in fine voice and treated NewsFour to a lovely rendition of Let Me Call You Sweetheart.

Mary adores him and sees him every other day. She regularly records him performing and posts the videos on the Ringsend People At Home and Abroad Facebook page, where he has plenty of fans.

Most evenings, Micko has a couple of whiskeys when he is watching football or doing puzzles and crosswords, another passion of his. He says, grinning, “I used to ate the beer, devour it” – back in the days when he drank with his good friends Bob Behan, Seamus Ferrari and Tom Dunne – “though I wouldn’t be able for that now.”

When he moved to the Ailesbury Nursing Home three years ago, after a long spell in hospital, he was happy to hear piped music playing in the background. He could hear it in the halls, in the lift, in the rooms, and it was always his favourite songs. Except, there is no piped music, the songs he hears are playing in his head. He is happy with that. As is Mary who says: “It gives me hope for old age, if the worst thing that happens is hearing the music you love all the time.”

By Jennifer Reddin