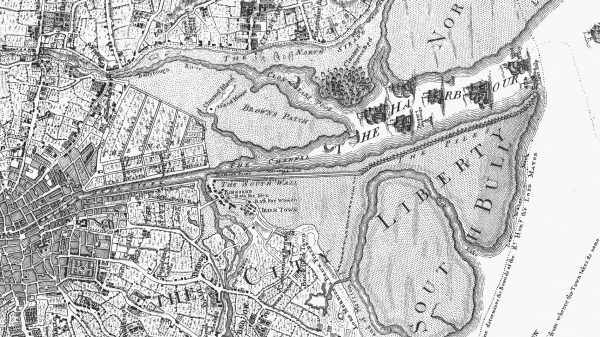

Above: This 1760 map by John Rocque shows the environs of Dublin Port at that time.

Dublin is an historic port city. Central to its evolution as Ireland’s most important trading centre is the River Liffey and the mercantile trade that developed around it.

For early settlers, the river’s estuary provided a substantial and easily defended harbour to the east and the flat plains to the west afforded easy access to the rest of the island, making the area an appealing place to set up home.

A thriving secular community existed on the south banks of the river, in the area around Wood Quay, before the arrival of the Vikings during the 8th and 9th Centuries. Downriver, a monastic community had been established close to where Trinity College now stands.

When the Viking invaders, and later the Normans, fortified the region, the city as we now know it began to take shape, with the river and the marine traffic it facilitated at its core.

Dublin’s wide bay was a notoriously dangerous place for shipping. Tidal dynamics caused the formation of large sandbanks in the harbour; a mixed blessing, they provided some degree of protection from invasion but shipwrecks were common. Nevertheless, by the 11th Century, thanks to trading links with England, Dublin prospered and it soon became Ireland’s most important urban centre.

Above: Historic River Liffey port trade near the Customs House.

In 1716, responding to demands for a resolution from the city’s merchants, Dublin Corporation established a committee known as the Ballast Office Committee.

The Ballast Office started work on what would become the Great South Wall in 1715. The project set out to protect the riverbanks on the south side of the channel at the mouth of the harbour, running from Ringsend to Poolbeg.

The original mud banks were replaced with the South Bull Wall in 1753, in the aftermath of a particularly stormy winter. When completed, it was the world’s longest seawall. On September 29th, 1767 the Poolbeg Lighthouse at the end of the Bull Wall was lit for the first time.

In 1781, John Beresford, First Commissioner of Revenue for Ireland, appointed the celebrated architect, James Gandon, to design a new Custom House. When it opened in 1791, the Port of Dublin and the axis of the city moved further downriver and trade and development started to expand on the north side of the water.

Despite the relocation of the port, sandbars continued to create dangerous conditions for shipping and the estuary was still extremely difficult to navigate. In 1800, Captain William Bligh (of Mutiny On The Bounty fame) recommended the construction of a Bull Wall to run from east-to-west, following a survey of the harbour. This, he believed, would prevent the build-up of sand in the bay. In time, Dublin Corporation decided to build the new wall southeast from Clontarf, which proved to be an enormous success.

The port grew steadily during the following years. George’s Dock was developed in 1821, providing large warehouses and storage vaults to form part of the Custom House Dock Area. During 1836, construction work began on deep-water berths at the North Wall. The North Bull Wall was completed in 1842. As predicted, it created a natural scouring action and the sandbar dropped by several metres over the following fifty years, making the river channel more accessible to trade vessels. Another outcome of its completion was the accumulation of sand along its side, which caused the creation of Bull Island.

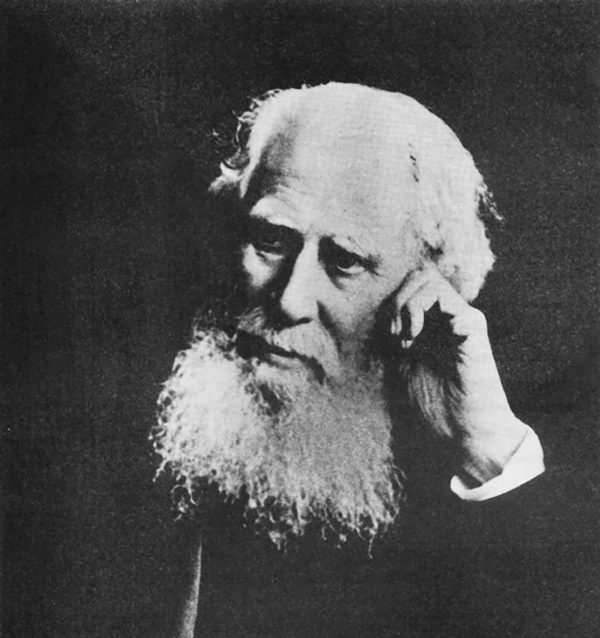

Pictured: Bindon Blood Stoney, progressive Chief Engineer in the 19th century.

He improved the channel between Dublin Bay and the city with a specially designed dredging plant and oversaw the construction of the North Wall Extension and the Alexandra Basin. He replaced the tidal berths with deep-water berths for overseas vessels, invented a diving bell and perfected the means to use precast concrete in construction. He is also responsible for the design of Grattan Bridge, O’Connell Bridge, and Butt Bridge.

Further deep-water berths in the Alexandra Basin were completed before World War One. Ocean Pier, to the south-east of Alexandra Basin, was opened shortly after World War Two.

Today, Dublin Port handles 44% of all port trade in the Republic of Ireland. As we look forward to the next stage of its development, with the publication of the Masterplan Review 2017, it is timely to remember with gratitude those long gone who gifted us such a valuable legacy.

By Jennifer Reddin