By Alexander Kearney

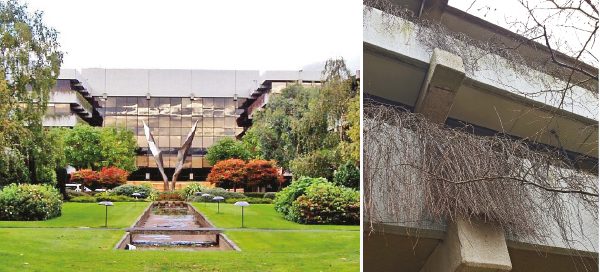

Then and now: The balconies, which used to teem with plant life, are bare.

We are fortunate in having in this country an efficient, stable, comprehensive banking and financial system of the highest integrity and probity.”

Even after nearly forty years, the nasal quality and slightly bored tone of the recorded voice are instantly recognisable. The words, as we would subsequently learn, were as false as the man who delivered them.

It was that financial system of ‘highest integrity and probity’ that continued to extend credit to a party leader who had no serious intention of repaying it, just as he announced to the nation that we, “as a community… are living way beyond our means”.

Yet on this occasion – 19th February 1980 – Taoiseach, Charles J. Haughey had something rather truer to say about the building he was opening, than about the institution, Allied Irish Bank, that had built it

The complex was, Haughey intoned, “The essence of good taste, discrete, neither imposing nor assertive, a fine example of the demanding art of orderly development. When the balconies are clothed in shrubs and plants we will have nothing less than the hanging gardens of Ballsbridge.”

As the RTE archive footage of the time reveals, the balconies were still bare, the landscaping stark and the planting more wish than fulfillment. Yet in time, the eight deferential-linked blocks would overspill with abundant growth, the ponds and central watercourse splash and glint in the sunlight, and the ample 15-acre grounds fill with trees and shrubs of almost edenic exuberance.

The AIB banking complex was, quite simply, the finest corporate campus in suburban Dublin. It was one of those rare modern buildings that was designed as a frame for nature, rather than to be its unrelenting master.

In this it perfectly reflected its creator, Andy Devane. Devane had the unusual distinction among his Irish peers of studying under 20th Century America’s most famous and celebrated architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

While other students could be overwhelmed by Wright’s colossal ego and idiosyncratic style, Devane learned just enough from the master not to be crushed by his example and to take precisely what he needed. The AIB complex doesn’t closely resemble anything that Wright built, but it is informed by his love of low, broad-branched forms in leafy settings, away from the piled-up chaos of urban life (Wright’s vision was essentially suburban, when it wasn’t explicitly rural).

Devane covered the surfaces of the balconies in pale grey mosaic – it was less likely to stain from planting – and wrapped the drum-like service attics in soft lead sheeting. All materials were considered as an unshowy foil to the mass of greenery that would soon envelop them.

Much of that greenery is now gone. The balconies, which used to teem with life, are bare and the central watercourse was removed a decade ago as part of a massive expansion campaign at the rear of the campus. The fine stainless steel sculpture, ‘Wings’ by Aleksandra Wejchert – still the scheme’s centrepiece – stands forlorn in a sea of granite paving.

Yet the real damage was ultimately done by AIB’s decision to hive off the front four blocks for future development in 2015. A previous attempt to demolish and rebuild the foreparts was rejected for reasons of overdevelopment, but the new buyer was not so easily deterred.

This was a resurgent Johnny Ronan, freed from his Nama shackles and determined to maximise – as he saw it – the value of his acquisition. After a lengthy planning battle, he has finally achieved that wish. The four, three and four storey blocks will soon make way for a scheme of far greater density and of much less sympathy to its neighbours.

This, at any rate, is the opinion of those residents on Serpentine Avenue who fought the scheme with grim determination, but who must resign themselves to two long six-storey glazed ranges overlooking a busy, sunken court. Haughey’s words – “discrete, neither imposing nor assertive” – do not immediately spring to mind.

Yet perhaps the most personal blow was to the immediate and extended family of Andy Devane, who objected to and then appealed the decision to grant redevelopment. In their eloquent submission, they make clear that Devane saw the complex as his culminating achievement, the very embodiment of an ideal he expressed in 1975 that, “In more ways than one, exterior space is the city dweller’s quotient of nature, his window of the seasons, yard-stick of the elements.”

The City Council and An Bord Pleanála were unmoved, and since last year the four dusty blocks have awaited their rendezvous with the wrecking ball.

Devane especially has been unlucky. His scheme was both the largest and least contentious of the three major Dublin bank building projects realised in the 1970s. Of these, perhaps the most polarising was the cantilevered stack of the Central Bank on Dame street by the pugnacious Sam Stephenson. Yet over time it has earned a certain grudging respect; it is audacious and it will certainly stay – in reality it was always too massive to make demolition attractive.

While the Central Bank has moved to new premises on the Northern quays, its old home is earmarked to become an office and retail hub with roof-top restaurant and bar. The former Bank of Ireland Headquarters on lower Baggot street by Michael Scott and Partners (subsequently Scott Tallon Walker) is now a protected structure and is viewed as the finest Miesian office complex in Europe – a work of exacting homage to Ludwig Mies van der Rohe; the creator of the Seagram building in New York, and the spiritual father of the steel and glass office block. That complex is nearing the end of a lengthy refurbishment that has verged on rebuilding, but on completion it will still recognisably be itself.

The Bank Centre of Ballsbridge has met a crueler fate, but one in some ways truer to the massive fall in prestige of the Irish banking system itself. The central banking authority, and the two leading retail banks it supervises, have essentially retreated from the ideal of creating their own built statements and instead slipped into the architectural shoes of others; in the case of the Central Bank, into the very carcass of what was to be the Anglo Irish Bank Headquarters, left abandoned and incomplete by that institution’s scandalous fall.

The dismemberment of the Ballsbridge complex represents the decisive end of that “demanding art of orderly development”, which must be seen as the better part of the banks’ legacy. Their ruin, and ours, was the bankrolling of reckless speculation by Ireland’s leading property developers. And in the case of Devane’s once gentle and leafy campus, it falls to a developer to administer the coup de grace.