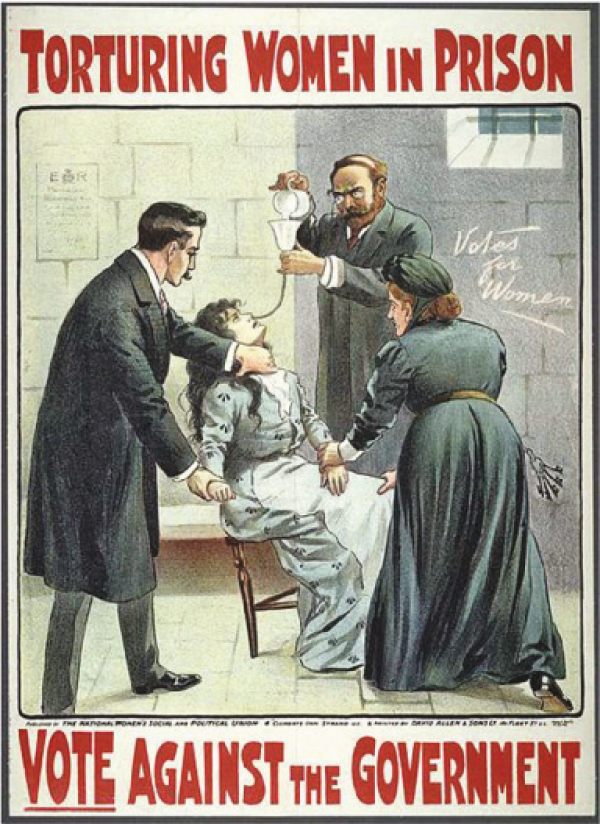

A poster used by the suffrage movement

By Eoin Meegan

This year marks the one-hundredth anniversary of women winning the right to vote, an event that has rightly been widely celebrated. To understand how this came about, however, we have to go back to the nineteenth century.

On the first suffrage petition to Parliament in 1866 by John Stuart Mill there were 25 Irish women signatures, among them Anna Haslam. She, along with her husband Thomas founded the Dublin Women’s Suffrage Association in 1876. According to historian Mary Cullen, the early pioneers of the movement were predominantly middle class, Unionist, and included a high percentage of Quakers.

The early suffragists used only peaceful means to achieve their ends, such as petitioning politicians and holding public meetings. Small gains were made, such as the franchise extended to local elections, but they were minimal. The term “suffragette” was first used in 1906, and as a slight, but was quickly appropriated by the leaders in the movement. In time it stuck.

By the first decade of the twentieth century a more militant faction spearheaded by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst began to emerge in Britain. Suffragettes were now taking to the streets, interrupting meetings, and chaining themselves to public buildings. “Deeds not words” became the clarion call.

A defiant insubordination began to manifest. This new development found traction in Ireland, only here there was the added complication of the movement becoming embroiled in the greater struggle that dominated Irish politics at the time, the demand for Home Rule. Predictable fissures began to show with some women calling for “No Home Rule before Suffrage,” while others opposed this.

Charlotte Despard, an English suffragette supported the 1913 Lock-Out in Dublin and Sinn Féin, while Christabel Pankhurst pronounced that Home Rule must be conditional on women getting the vote. Any alignment with suffrage movements from England was viewed in certain quarters with suspicion. More alarming, perhaps, were divisions between Unionists (predominantly from the North of Ireland) and Nationalists within the movement.

Some thirty years after the Haslams, and now more radicalised, another husband and wife team, Hanna and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington had, along with Margaret Cousins, established the Irish Women’s Franchise League. Sheehy-Skeffington was a complex figure. Although from a strong republican background, she didn’t believe the woman’s cause should be subjugated to the nationalist or any other one.

She was highly critical of John Redmond when suffrage for women was absent from the third Home Rule Bill, and for voting with Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith in defeating the Parliamentary Franchise Bill of 1912. She famously smashed a window in Dublin Castle that year for which she, along with fellow activists Margaret Palmer, Jane and Margaret Murphy, and others went to prison.

Sheehy-Skeffington challenged the authorities for allowing loyalists to arm with impunity while women were imprisoned and tortured (force fed when on hunger strike) for what amounted basically to civil disobedience. She was fiercely anti-Treaty, but was also disappointed in De Valera and thought the constitution helped retain the sub-par status quo for women, especially Articles 41.2.1 and 41.2.2., and was discouraged at what she saw as the gradual erosion of hard-won rights for women.

She wrote, “until the women of Ireland are free, the men will not achieve emancipation.”

In 1911 Louie Bennett and Helen Chenevix founded the Irish Woman’s Suffrage Federation, an amalgamation of smaller suffrage groups, and the Irish Women Workers’ Union in 1916.

Two years later it was officially recognised as a trade union with over 5,000 members. They opposed the cessation of activities when the war broke out, as did a number of other prominent suffragettes, including Belfast woman Margaret McCoubrey. Until her death in 1963 Chenevix campaigned tirelessly for women’s rights, as well as for world peace and nuclear disarmament. Eva Gore-Booth, sister of Constance Markievicz was heavily involved, and Cork woman Cissie Cahalan argued as early as 1919 that women be given equal pay for equal work. Definitely ahead of her time.

The suffrage movement may have been put on hold with the outbreak of the war, but by then there was almost an inevitability about the outcome. Doubtless, the campaigning helped raise the consciousness of women, as well as a broader awareness of a demonstrably unequal and rigged system.

At the same time, women were increasingly becoming a presence in the workplace, very often carrying out tasks that would previously have been closed to them, such as driving ambulances and being employed in the manufacture of ammunition. Here, for example, the Liffey Dockyard Munitions Company employed local women. It is impossible to say what, or how quickly, advances would have happened had not the war intervened. But the courage, grit and bravery shown by women at this time, I think, sealed the question for good.

On February 6, 1918 the Representation of the People Act finally delivered women, with property, and over 30 years of age, the vote. The election of Constance Markievicz as the first female Member of Parliament at Westminster in the general election which followed in December was a great symbolic victory for the suffrage movement and a particularly proud one for Irish suffragists. She would later become the first female TD and Cabinet Minister to serve in the Dáil, something that would not happen again until Máire Geoghegan-Quinn was appointed Minister for the Gaeltacht in 1979, a hiatus of 57 years, which, unfortunately, gives weight to Sheehy-Skeffington’s disillusionment.

It must be noted the Act also granted the vote to all men over 21, including those in the armed forces, regardless of whether they owned property or not. So while undoubtedly a momentous occasion for the struggle that began with petitioning and letter-writing more than half a century earlier, it still left women short. Reason to celebrate yes, because some women actually got the vote, but the Act, as we saw, gave more to men.

This imbalance was redressed here in 1922 by the Constitution of the Irish Free State, Article 41. Women in the UK would have to wait another six years before receiving the same in 1928. So, in this instance at least, we see the new fledgeling State that was Ireland leading the way in political and social reform. All in all, a cause for celebration, not only for women, but echoing Sheehy-Skeffington, for all humankind.