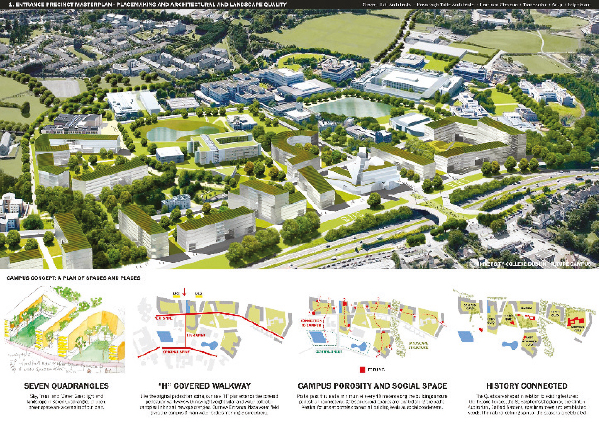

A bird’s eye view and concept images for the new UCD ‘Future Campus’ Master Plan by competition winner Steven Holl (UCD and Malcolm Reading Consultants).

By Alexander Kearney

When the American architect, Steven Holl was announced the overall winner of UCD’s Future Campus Master Plan competition early last August, it’s fair to say the reaction in the wider architectural community was mixed.

He had prevailed in a two-stage contest against 98 teams from 28 different countries, yet still there were expressions of disappointment. Not because Holl isn’t known; he is, in fact, very well known. At 70 years old, he is at the peak of his profession, with offices in New York and Beijing. And not because Holl isn’t a very able architect; he is frequently bold and occasionally brilliant.

The reasons are various, as we shall see, but they begin with a perception that his entry, including a concept for a new 8,000 sq. metre Centre for Creative Design, was a superficial medley of forms and influences, pandering to its intended audience. As one prize-winning Irish architect sharply put it on Twitter, “This wouldn’t pass second year in most European schools of architecture.”

Members of the international competition jury, of course, took a different view. The Jury Chair and President of UCD, Professor Andrew Deeks declared, “Holl’s vision is intriguing and striking… The Centre for Creative Design promises to be an exhilarating presence, announcing UCD from afar, creating a new Dublin landmark, and giving visitors, students and faculty a definite sense of arrival.”

Another jury member, Professor of Architecture at UCD, Hugh Campbell, said, “Holl’s winning proposal combines the striking form of the Centre for Creative Design building with a clear and robust masterplan.”

If criticism of the winning entry had been merely confined to aesthetics, then the debate might have remained in the rarified worlds of architecture and academe. However, those concerns now extend to the composition and decision-making of the international jury, and what these reveal about UCD’s approach to governance, campus planning, and gender equality. If the Future Campus brief represents UCD’s vision of itself, it also raises serious questions about how it intends to get there, and just how closely the jury studied the winner’s plans.

Doubts about that jury were shared on social media as news of Holl’s win came in: the focus was on the relative lack of women. As one poster put it, “Two women out of 12 panelists is a bit crazy especially when Irish female architects and architecture writers/critics are doing so well. Maybe there simply aren’t enough women in big business and property development?!”

Among the jury panel were Dermot Desmond, Chairman of International Investment and Underwriting (whose Shrewsbury Road house plans are assessed elsewhere in this issue), and property developer, Seán Mulryan. Also adjudicating were leading architect David Adjaye, responsible for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington DC, and Malcolm Reading, architect and Director of Malcolm Reading Consultants, the organisers of the competition.

The two women on the jury were Amen Beha, Principal of Boston-based Amen Beha architects, and Orla Feely, Vice President for Research, Innovation and Impact and Professor of Electronic Engineering, UCD.

Another online commenter remarked that, “Perhaps they need to reread their UCD Gender Equality Action Plan 2016-2019.” And indeed, UCD has such a plan, as part of a higher education requirement that allows it, and other third-level bodies, to apply for various forms of research funding.

The following sections of UCD’s own Action Plan seem to be relevant: Point 4.8, ‘Supporting and Advancing Women’s Careers’, states, “Selection committee membership, and their Chairs, will consist of at least 40% women and at least 40% men (comply or explain)”, and, 4.4, ‘Organisation and Culture’, adds that, “Chairs of all committees to report on implementation (comply or explain).” The balance on the International jury was just over 16% female, or nearly 84% male.

NewsFour made repeated enquiries to UCD’s office of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI), asking whether it had been consulted on the competition, and whether the jury panel came under the university’s much-vaunted Action Plan. We were eventually referred to the UCD Communications Office with a one-line acknowledgment. By then, the Communications Office had replied to a similar set of questions with the following emailed statement: “The University undertook its best endeavours to have a gender-balanced panel… the relevant roles from within the University structure are all currently held by men – (College Principal for Engineering and Architecture, VP for Campus Development and Dean of Architecture). The University was disappointed that a number of women invited to be on the competition judging panel were unable to give the time commitment.”

Neither the EDI nor the Communications Office were prepared to answer whether the Action Plan applied to the jury, or just why problems of time-commitment should disproportionately affect women. Nor is it clear how many women candidates were approached for the panel; a direct question on the subject was still left unanswered at the time of writing (UCD explained its Director of Communications was currently on sick leave).

The above might be considered a rather abstract row over gender quotas, were the sheer disparity between stated commitment and actual representation not so glaring. The rapid rise of Irish women within the fields of design and architecture should have ensured that the university met its minimum targets with relative ease. Whatever else UCD’s priorities might have been in gathering its competition panel, gender equality doesn’t seem to have been high among them. A case of better said than done.

And what of the winning entry itself? The focus of criticism by other architects has been on Holl’s concept for the €48 million Centre for Creative Design. This is the building intended to announce UCD to its Stillorgan road entrance (R138) and environs, and to bring together various creative and technical fields in cooperative endeavour. Holl’s proposal is for a glass and metal-clad building, sprouting three cranked funnel-like towers and a large dodecahedron auditorium, the latter a nod to UCD’s best known landmark: its 1972 concrete water tower. Holl’s building is full of such nods. In one pictogram he includes a photograph of the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim and a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses as inspirations for the centre’s form and subtext.

For several critics, this was simply too much. Architect Sean Griffiths took aim at Holl’s pretentions in Dezeen, a leading online design magazine. He wondered if Holl had, “metaphorically marauded across the landscapes of the emerald isle and, in doing so, failed to spot a couple of not unimportant details. Firstly, the geographical inconvenience that the Giant’s Causeway is not, in fact, anywhere near Dublin, and secondly, the unfortunate faux pas of neglecting to notice that the world-famous landmark is not actually situated within the borders of the country of which Dublin is the capital.”

This is perhaps unfair to Holl who, elsewhere, has shown a rare gift for reading site and terrain. In at least one instance, he overcame a seriously flawed brief to deliver a memorable, even inspiring project. Visitors to his additions to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, still enthuse about the necklace of glowing pavilions that slink past the original 1930s beaux-arts centre-piece. And Holl won that competition in defiance of the official brief. There, he took the bold decision to place his buildings where he thought they should be, rather than where the museum had specified they should go. None of the other finalists showed such pluck, and the assessors were unanimous in awarding a rule-breaking Holl the commission.

It is perhaps surprising then that there should have been so little comment on the bigger part of Holl’s UCD entry: his master plan for 23.8 hectares of the North Eastern side of Belfield. Holl’s outline calls for seven new, open-sided quadrangles linked to the existing campus core via a H-plan network of translucent glass walkway canopies. These canopies would collect rain rainwater and generate solar power, thus advancing UCD’s aims to promote greater green measures and technologies. They take their cue from the concrete sheltered walkways, which form the spine of the original 1964 competition-winning campus masterplan by Andrzej Wejchert, a then unknown 28 year old Polish architect.

Yet on studying the new master plan, questions mount as to how closely Holl and his team actually looked at the present-day campus. What has so far gone unremarked in news coverage is that the main aerial and satellite views in Holl’s winning presentation are significantly out of date. They omit several major changes to the campus core that have taken place over the past decade, or are now taking place. And those changes are immediately adjacent to the area covered by Holl’s master plan.

Perhaps the most salient of these is the new UCD ‘Club’ annex to the O’Reilly Hall, which doesn’t even appear in the winning submission, though it is currently under construction. No trace of the ‘club’ can be found in Holl’s renders, plans, or illustrations. Nor do recent large additions to the Science block (completed in 2014) feature in Holl’s satellite view of the campus.

Some faint CGI indications of changes to the original buildings do appear in his main aerial view, but not as built. The current footprint of the O’Brien Science Centre is, though, indicated in Holl’s smaller diagrammatic plans. The position of the recently completed Confucius Institute is noted throughout Holl’s submission.

What is curious is that, despite the winning entry going through several rounds of assessment, such omissions apparently weren’t caught or corrected in consultation with the jury. In the second round, Holl’s scheme competed against just five other entries. The finalists toured the campus, received further briefing, and were interviewed by the panellists. It is all the more surprising, then, to observe the connections between the buildings left out, and those members of the jury who commissioned them or otherwise oversaw their construction.

The missing UCD ‘club’ annex has been widely reported as a campus priority of President Deeks, and President Deeks was the jury chair. The project to realise the new Denis O’Brien UCD Science Centre, though strangely absent from Holl’s satellite and aerial images, was personally overseen by Professor Michael Monaghan. Professor Monaghan is vice-president for campus development, and also served on the jury. In addition, the panel included three other faculty members, among them Professor Hugh Campbell, Dean at the School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy, UCD.

It is perhaps worth noting that only one other of the six finalists omitted the new UCD ‘club’ from its entry (Studio Libeskind). But Libeskind and the other finalists did include all the other major campus updates in their presentation materials. When I asked Dublin City Councillor, Dermot Lacey, who sits on UCD’s Governing Authority, what he thought of Holl’s omissions, he said, “The absence of the visuals as you describe does seem strange, but I would hope that the judges would have been able to use their knowledge of the site when making the decision.” One may hope.

To be clear, Holl’s omissions don’t invalidate his Master Plan, but they do affect its context, and arguably some of its assumptions. For instance, the new ‘club’ building blocks the straight path of a secondary pedestrian route indicated in his plans between the new ‘Oakland’ quad and the central lake. And Holl’s principal aerial image, taken from the far side of the Stillorgan road, betrays no sense of the closed and massive form of the main O’Brien Science building as it now stands.

It is that last image that bears some scrutiny when asking precisely how Holl and his team came to use such outdated imagery. For the Future Campus competition is not the first time UCD has tried to put shape on an area stretching between its campus core and the Stillorgan road. The Gateway Master Plan competition from 2006-2007 had similar, sweeping aims, but ultimately foundered in 2010, when the realities of global recession overwhelmed it. A great deal of money was spent (a reported €10 million in consultation fees), but nothing from this plan was built.

Yet some of its presentation materials do seem to have been revived for a second use. On close examination, Holl’s team appear to have copied and pasted their scheme over a minimally-adapted background image from Christoph Ingenhoven’s winning entry for that previous Gateway Competition. Holl’s bird’s-eye view shares the same ghostly render of future additions to the Science Block, and inadvertently includes a fragment from Ingenhoven’s proposed extension to the rear of the O’Reilly Hall.

The above is certainly not evidence of plagiarism (Holl’s scheme hardly resembles Ingenhoven’s in any other respect), but of Holl’s haste in preparation. What it reveals about the jury is less certain. It has not been revealed whether the final choice was unanimous, or how close that decision actually came. Did Holl’s anachronisms entirely escape their notice, or was the view taken to dismiss these as trifling oversights on the path to the grander things? And what else might the jury have missed, or perhaps preferred to take on trust?

Holl’s master plan begs many questions. How practical will the upswept angles of his proposed glass-topped walkways be in driving Irish rain? Will they end up being cracked receptacles for dead pigeons and lost running shoes? And do Holl’s rather vague plans for burying two car parks, and creating a submerged motor entrance from the N11 slip-road, provide an effective basis for rethinking UCD’s approach to traffic. Holl’s vision here is arguably not broad enough.

A runner-up proposal by John Ronan makes a bolder go of it, by envisaging a traffic plan for the larger campus. The new master plan lays out seven generous open-sided quadrangles, but what lasting measures will be taken to ensure that these are not progressively filled in? The main O’Brien Science building, the one that doesn’t appear in Holl’s renders, is an example of precisely this kind of creeping development.

But before any of this, there is the apparent lack of a budget for the master plan, or at least one that has been made public.The total sum for the abandoned Gateway project was pegged at €450 million, nearly ten times the estimate for the new Centre for Creative Design. UCD has yet to clarify whether any figures for the master plan were discussed or circulated with entrants to the Future Campus competition. The worry must be that as the university gains a shiny new addition, it will struggle to implement the rest. Or implement it in ways Holl might never have intended.

Finally, it’s worth thinking about the historical context for the Future Campus initiative. It is highly unlikely that a young Andrzej Wejchert would have been eligible for the Future Campus competition, even though he conceived the original campus layout. He certainly wouldn’t have met the criteria for the Gateway project, whose terms explicitly stated, “Firms must have successfully completed prime consulting contracts for major capital works in excess of €50,000,000.”

The story goes that Wejchert drew up his winning proposal on the kitchen table of his mother’s flat in Warsaw, poring over maps of the Belfield site and imagining the campus terrain. His first visit to Ireland was made only after he had won the competition. Yet his vision still remains the most coherent of any of the plans drawn up for UCD. The subsequent departures from it are to be lamented, especially the succession of moves away from a tightly integrated spinal corridor. Perhaps the new ‘Master Plan’ will restore a sense of focus to the campus, but its network is looser, and its buildings and spaces considerably larger than those in Wejchert’s original scheme.

Holl, by contrast, has many projects on his books, ranging across the United States, Europe, and China. He frequently works while flying, emailing notes and sketches to his offices on opposing sides of the world, as he travels from one commission to the next.

The geographical distance between the Giant’s Causeway and Dublin must appear rather small from such a vantage point. And at 38,000 feet, or in a far-away studio, allusions to Joyce and geology might feel more urgent and real than the very buildings that continually seem to sprout over a now sprawling Dublin campus.

One must hope that as the plane descends, and detailed plans are summoned, that the eye will become more firmly fixed on the facts on the ground, and on the living terrain of his first Irish commission. For this, and much else, the jury remains out.