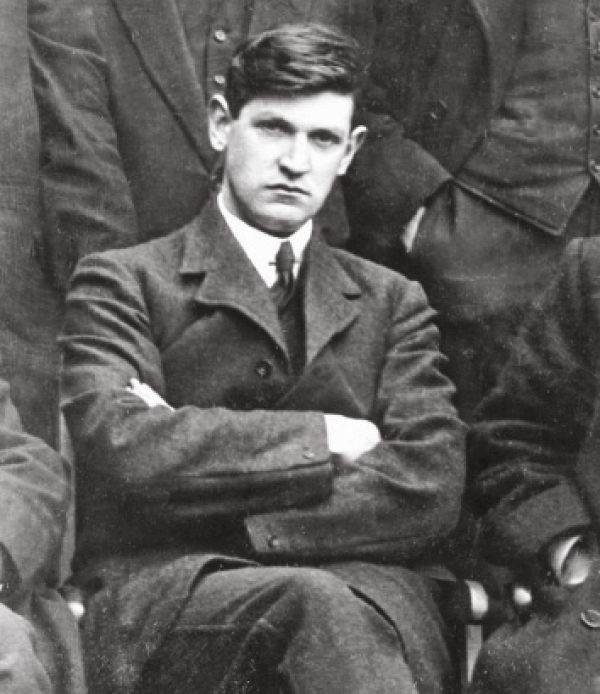

Image courtesy of Wikicommons.

By Eoin Meegan

With 2020 only weeks away, Ireland will shortly enter the centenary of a particular day and event that could be said to have changed the course of the War of Independence, tipping the balance in Ireland’s favour: I speak, of course, of November 21st 1920, the day which came to be known as Bloody Sunday.

Three separate events mark that fateful day. The first was the virtual annihilation of the ‘Cairo Gang’, a select group of British intelligence agents who were sent to Dublin to infiltrate the IRA, gather intelligence, and assassinate leading members of the newly formed Dáil, which the British government had declared to be “a dangerous association.”

Michael Collins, however, had set up his own counter-intelligence unit, and created a strike unit known as the Squad, which also went by the name of the ‘twelve apostles’. Collins had amassed a network of contacts and spies throughout the city which included chambermaids and porters, policemen and couriers, even penetrating Dublin Castle itself. His ambition was to destroy the entire British intelligence network in Dublin and bring the British government to the negotiating table.

At 9.00am that Sunday morning the Squad entered 28 Pembroke Street killing three members of the Cairo Gang. A second target, Lieutenant Donald Lewis MacLean was shot dead at no 117 Morehampton Road, Donnybrook. Others were to follow at addresses in Baggot Street, Mount Street, Earlsfort Terrace, the Eastwood Hotel, Leeson Street, and the Gresham Hotel.

In all, Collins’s Squad left fourteen dead and five more wounded. While the operation was hailed a success, some of their targets escaped, including intelligence specialist Charles Peel, who managed to barricade his bedroom door at 22, Lower Mount Street until a group of auxiliaries arrived from nearby Haddington Road.

At least one person was killed in error, which Collins later acknowledged; Patrick McCormack, one of the residents at the Gresham was a member of the Veterinary Corp and not part of the Cairo Gang. Only one Squad member, Frank Teeling, was captured that morning and later he escaped from prison. However, the morning turned out to be a crushing blow to British intelligence in Dublin, and while they did recover, it marked a decisive turning point in Anglo-Irish relations.

Later that day a challenge match was scheduled between Dublin and Tipperary footballers at Croke Park at 2.45. There was a heavy contingent of police and Black and Tans outside the ground in the lead-up to the match, and many people were expecting trouble, because of what happened that morning.

In fact the IRA gave the order that the match should be cancelled, but the call came too late and the ground was almost full. Not wanting to cause a panic and a rush for the exit gates, and perhaps asserting the GAA’s independence, the general secretary of the GAA Luke O’Toole decided it should go ahead.

Soon after the match had begun, and following what seemed like a signal from a British army plane flying overhead, RIC officers accompanied by Auxiliaries burst into the grounds and began firing indiscriminately into the crowd. In the moments that followed, panic and terror filled the park. People were screaming and trying to run to find cover.

In total, fourteen civilians, including Tipp player Michael Hogan, whom the Hogan Stand is named after, were killed. Included in the carnage were two children aged ten and eleven, a fourteen-year-old boy and a young woman, Jeannie Boyle, who was due to be married in a few days’ time. Over eighty people were injured, some seriously.

The reason given for the invasion was to search the crowd for weapons, but it’s hard to see it as anything other than a reprisal for the embarrassment the British forces suffered that morning. It should be said that the scene in Neil Jordan’s film Michael Collins where an armoured car is driven onto the pitch and fires into the crowd never actually happened. The armoured car remained outside the stadium on St James Avenue.

Finally, as night fell over an eerie, locked-down city three prisoners were shot dead in Dublin Castle; Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, both members of Collins’s Squad, and Conor Clune a civilian who had been arrested with them.

The authorities in the Castle put out the story that because the cells were all full, the men were left in a room that contained ammunition which they seized and attempted to escape, and in the ensuing battle all three were killed.

This story was carried by a large contingent of the English press, but turned out to be one of the first examples of ‘fake news’ anywhere. Not only did a shoot-out not take place, but when the three bodies were returned to their families there was evidence they had been tortured and summarily executed, in retaliation, no doubt, for the morning assassinations.

The events of Bloody Sunday, along with the sacking of Balbriggan exactly one month earlier, and the burning of Cork in December, all coming on the heels of the Amritsar atrocity in the Punjab, just a year previously, saw Britain’s credibility and international standing at an all-time low, and support for Ireland’s cause gaining momentum in the US.

November 21th 1920 may be seen as a turning point in British rule in Ireland. Undoubtedly, it was an important factor in Prime Minister Lloyd George calling a truce the following year, which Michael Collins wanted. The truce was signed on July 9th 1921, coming into effect two days later. It brought hostilities to an end on both sides and led the way to the eventual setting up of the Irish Free State.