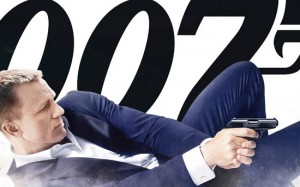

At the end of their first meeting in this new incarnation of Bond, Ben Winshaw’s Q turns to Daniel Craig’s 007 and asks, “Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don’t go in for that anymore,” tells you quite a lot about this leg of the spy series. James Bond celebrates half a century with the new film Skyfall. The gadgets are subtler, the story draws on real life concerns, while the ladies are more than playthings – clothed (for the most part).

At the end of their first meeting in this new incarnation of Bond, Ben Winshaw’s Q turns to Daniel Craig’s 007 and asks, “Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don’t go in for that anymore,” tells you quite a lot about this leg of the spy series. James Bond celebrates half a century with the new film Skyfall. The gadgets are subtler, the story draws on real life concerns, while the ladies are more than playthings – clothed (for the most part).

In fact the only boobs I saw were in the audience, chortling with discomfort at the homoerotic subtext of Javier Bardem’s terrific villain Silva. That being said, Sam Mendes’ intriguing debut as an action helmer gets rather entangled in its desire to sate so many tastes. It is not only not a traditional Bond flick, it is not a wholly new creation either, making fudged reference to the series’ lineage and half hearted stabs at the coy interplay between Bond, the babes and the bad asses.

It’s an intelligent and enjoyable addition to the cannon that proves that its producers are at least trying to keep it relevant to these grim times without throwing out what made it so special in the first place. But those telling you it’s the best Bond yet, or worse, Oscar worthy, most likely have little experience of the series pre-Brosnan or movies made prior to the turn of this century.

A passable pre-credits action sequence sets up the spine of the flick, which asks us to consider the cost of a human life. Something M (a stunningly good Judi Dench) must weigh up as Bond does his usual pre-credits shtick. A car chase becomes a fist fight on top of a speeding train as bullets fly, bodies roll and a field agent (an overly ironic Naomi Harris) tries to get a clean shot which will take out an enemy who has, in his possession, the name and location of all of NATO’s undercover operatives.

Needless to say it doesn’t go well and as Bond is sent to find out the identity of the maniac who is slowly unearthing the moles and who has blown up the head office of MI5, the conflict between the old and new way of doing things in the intelligence community is paralleled by the challenges facing this movie, which itself is trying to adapt to changes in how Bond should be presented.

For all intents and purposes fantasy is dead. While once it was the cartoon aesthetic that wowed the audiences of the Batman flicks, or the suave sophistication of yesteryear’s Bonds dispensing with caricatured Russians in their volcanic hideaways, a side of reality is now ordered with our action pie. We’ll accept our heroes to have super strength and be seemingly impervious to bullets to a point, so long as it doesn’t feel like too much of a stretch. As long as we can relate it to what’s going on in the world today and as long as we get to see the gin soaked psychological scars.

And so it is here, with a mentally and physically spent Bond, whose past is brought centre stage for the spectacular showdown at the movies end. We are given an interesting riff on the relationship between M and her double-0s, shown how the threat of bureaucracy is almost as dangerous as the one posed by the enemies ‘we must fight in the shadows’, and through Roger Deakins stunning cinematography, it is implied that the East is rising while the West crumbles.

But it doesn’t dwell on these points; rather circles back upon itself, rehashing tired Bond formulas. Rather than tackling the question as to whether there is a need for characters like Bond and M in the 21st century, it takes dead-end detours to exotic locations despite the fact that the more claustrophobic action sequences in London are some of the best the series has ever had. Rather than fleshing out the antagonism and betrayal that underscores Silva and M’s relationship, and which tie him to Bond, the movie plums for improbable escapes or diversions from death so well mocked in Austin Powers.

While – more worryingly for a filmmaker of Sam Mendes’ stature – its turns were met with audible moans from the audience since they hung on improbable mistakes made by characters; something as simple as using a torch when you shouldn’t or forgetting to close a door might be excusable in mere mortals but in super spies purportedly on top of their game, they jar.

In Silva, Skyfall does possess the best villain the series has had in years, with Bardem mincing outrageously in front of the uber-straight Bond and revealing the cost of serving ones country when it does not serve you. He is an affront to everything Bond believes in and his opening monologue is gorgeously shot, enveloping us with camera trickery and gory verbal imagery. Arriving one hour into the action, he brings the picture to life.

The rest of the new cast (Harris, Ralph Fiennes) however, are depressingly one note, all there to provide fodder for a reveal that people with guide dogs could see coming while the scars left by Vesper Lynd are still raw as the Bond Girls have been sidelined yet again. There’s a blink and you’ll miss her turn from Berenice Marlohe, who brings nervous, manic energy in an under utilised role, which I hope, the film makers wanted to use to contrast Bond’s detachment with M’s own cavalier disregard for her agents so that she can go on making the decisions that keeps the world, or at least the Empire, safe.

When left to be himself Craig is an excellent Bond. Able to credibly pass as a riled up action hero, a weary agent or a bemused man-child, his biting tongue spilling acid over the more louche delivery of previous incarnates. His interplay with M is genuinely engaging; there is a sense of something being at stake. But he struggles when he is called upon to deliver the punchier dialogue – the sherry and slippers slapstick of Roger Moore, the affable asides of Pierce Brosnan – so that you have to wonder why they try to soften his edges.

If they are ever to make the Bond that is truly relevant to the now they are going to have to shake of the ghosts and whispers of those gone by who flicker throughout this movie like the figures in its opening credits and really get under the skin of this damaged character to make his treatment of women and his dedication to the job ring true.

The dire Adele theme tune sums up what’s wrong with an otherwise worthy picture. It pays too much lip service to themes gone by, and in trying to fit into a familiar formula it can never truly be itself. It has the horn but lacks the honk. One needs to make its peace with the other for the series to progress.

By Caomhan Keane