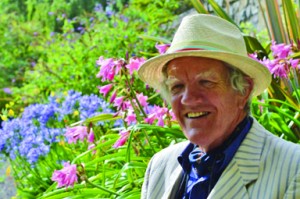

Built on reclaimed land, and located on the Strand Road in Merrion, the home of Charles Lysaght – historian, biographer, barrister and obituary writer, is steeped in history. The social and geographical landscape of the area has changed since Charles’ childhood – Leveret and Frye in Sandymount have been replaced by Tesco, Mr De Valera no longer strides up and down the strand on his daily visit from nearby Booterstown, but for him the past is everywhere alive in Merrion.

A lot of the houses and roads are exactly the way they were when Charles was a child. The people are different however, “I suppose the social composition has changed, it’s become completely a middle class or upper middle class area. When I was growing up there were big houses and ‘artisan dwellings’, there was a better mix of people, and everyone knew each other.”

Reclamation in the area started in the 1700s, and stretched as far inland as Donnybrook. One of four regency villas was built in the mid-19th century by the O’Brien family (of Johnson Mooney and O’Brien fame). The house had been lived in by a succession of people, including former chief of staff of the IRA Dr Andy Cooney in the 1930s. During Cooney’s time there, a court martial of Sean Russell was held in the house by Sean McBride, then chief of staff of the IRA.

Given that his family home is steeped in such prestige, is it any wonder that Charles would dedicate a significant amount of his life to history. After graduating from UCD, he went on to study in Cambridge University, where he became president of the Cambridge Union, beating Vince Cable (currently a Liberal Democrat minister in the British government) in the election to be head of the famous college debating society.

During his time in London, Charles was asked by The Times of London to write obituaries of prominent Irish people. At any given time he has about a dozen ready to go, or in the process of being researched. Obituaries are never signed, and Charles explained that it gives the writer more freedom to give a more rounded picture of a life.

In conjunction with The Times of London, Charles edited a collection of obituaries, many of them written by himself, called Great Irish Lives. The book covers The Times obituaries of Irish politicians, artists and literary figures stretching from Henry Grattan to Nuala O’Faolain. The anonymity of an obituary writer not only gives the writer freedom, but also some authority, according to Charles. He says occasionally relatives can be annoyed at what is written.

“There is a great culture of the gushing eulogy in Ireland. We may not speak well of the living but we speak well of the dead – a gushing eulogy does nobody any justice as we are all ‘light and shade’.”

I asked Charles what he would like to see in his own obituary. He said he is often asked that question, but that he simply doesn’t know and says he hasn’t thought of it much. “I sometimes think I should write it to help them out!” Charles says that unlike the people he writes about, his own life has not changed the course of history. “I have lived a life on the sidelines, commenting on things.”

Charles Lysaght has spent much of his writing life recording the lives of people who have made history. While lecturing in law at London University, Lysaght became interested in the mysterious life of Brendan Bracken and went on to write a biography of the Irishman who became the most trusted colleague and great friend of Winston Churchill.

Brendan Bracken was the son of a Tipperary stonemason. His father was a republican and one of the founders of the GAA. Brendan’s mother sent what the Old Limerick Journal in an article entitled Brendan Bracken – The Emergence of an Imperialist called “her troublesome son” to Australia as a teenager. He found his way back to England some years later. He talked his way into a British public school by telling people that he was an orphaned Australian whose parents had died in a bush fire. He worked as a journalist and went on to become an MP and was spin doctor for Winston Churchill during the war – although the term had not been invented.

Because of their closeness, and their shared red hair, there were always rumours that Bracken was Churchill’s son. Churchill reportedly said many times that he wished it was true – much to the annoyance of his actual son, Randolph.

It is to Lysaght’s credit that Bracken’s biography was written at all. Bracken had left orders that his personal papers be destroyed after his death. It took his driver Alexander Aley a full week to burn the documents. Charles explains Bracken’s contrary attitude in his biography: “… his sense of past was not accompanied by a reverence for the materials out of which history is made.”

By Ruth Kennedy