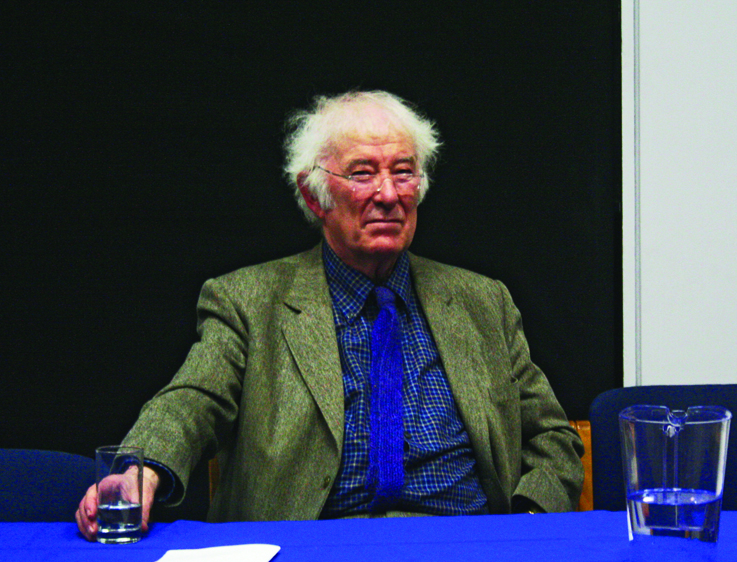

My original intent for this month’s Poet in Profile was seasonal – I was on the lookout for a writer of Hallowe’en or spooky poems, someone with a whiff of brimstone in their work for this corner of the year. And then, abruptly Seamus Heaney died.

Nobel laureate, lecturer, translator, Heaney was a towering influence of modern letters. His career spanned decades, from the early sixties in Belfast, where he began to write and publish his poetry in his spare time, to the publication of his last collection The Human Chain in 2010 and his donation of his personal literary archive to the National Library in late 2011.

Personally admired by those who encountered him, if not universally lauded within the contentious world of poets and their critics, Seamus Heaney was – and still is – a figure that three generations of poets have had to define themselves in relation to. NewsFour reached out to some verse-smiths to hear their thoughts on the late poet.

The first port of call was our previous Poet in Profile, Noel Duffy. In the lengthy interview conducted for that article, Noel mentioned Heaney frequently as a formative influence. He was happy to expand further, “I started to write just out of college, around 1993, and at first I was writing very impressionistic stuff, putting down my feelings. Then the poet Pat Boran introduced me to Heaney’s collection Seeing Things. After that, it really clicked with me that poems have to have concrete images. That was a penny-drop moment for me.”

Heaney was at times criticised for a perceived evasiveness around issues of Irish sovereignty and the North, his supposed refusal to take a side or address the matter at length in his written work. However, Noel invites the curious to consider the 1975 collection North. “The language in these poems is almost entirely stripped of the Latinate elements of English. It’s very Anglo-Saxon, curt and guttural, and the subjects are tribalism and Iron Age ritual killings. Punishment in particular, has resonances with the Troubles, which were at a frenzied peak around the time of publication.”

“But,” Noel adds, “the first and last poems of the collection Moss Bawn and The Singing School are about civility and subtle shows of mutual respect. That seems significant to me.”

Further afield, NewsFour contacted Patrick Chapman, poet and screenwriter, whose most recent collection A Promiscuity of Spines: New and Selected Poems is available now from Salmon Press.

“I met him briefly once at a reading he gave, and he was lovely. My only anecdote is oblique. Back in 1995, my then-girlfriend and I were in line to check in at Dublin Airport when we saw Seamus and his wife ahead of us. The Heaneys, we read later, were bound for Greece. That was the holiday they were on when his Nobel win was announced. I like the idea of that: being away on a remote island when Oslo calls you up. It seems fitting for a poet.”

Regarding the work, Patrick highlighted the poem Mid-Term Break as a personal favourite and a crucial influence. “It stirred something in me as a child, my first intimations of mortality, and the power of language. There seemed to be no difference between the medium of the poem and the reality it imparted.”

In Sandymount, reaction to Heaney’s death has been sincere, although for many the man was hardly a constant face about town. Joycean and poet Rodney Devitt expressed regret that he and Heaney’s paths never crossed, and felt it notable that such a celebrity was content to be a quiet presence. Rodney’s favourite is probably the most famous of all, 1966’s Death of a Naturalist.

In Sandymount, Heaney’s collections of poetry are selling strongly, according to proprietor Brian O’Brien of Books on the Green, with new print runs on the way. If you’ve never read Heaney, or it’s been a while, now might be the moment to rediscover this literary icon.

By Ruairi Conneely