It being the time of year where people have sworn themselves to new habits, the word meditation gets bandied about quite a bit.

Resolutions may come and go as January blends into later months but advocates for this ancient practice never seem to rest. It’s one of those things, like juice fasts and veganism that seem to make extreme converts. So what’s all the fuss about, and does meditation have concrete benefits?

Meditation is traditionally associated with religious practice, particularly in the Far East. In the last decade or so, a boom in the development of brain sciences has led to a deeper understanding of the physical benefits of silent concentration practices. Better brain-scanning technologies have shown that even inexperienced or first time meditators experienced a measureable change in brain wave activity: ordinary waking awareness (Beta) begins to incorporate activity associated with deep states of relaxation (Alpha), openness and self awareness (Theta).

In a modern environment of constant, now portable distraction and stimulation, one of the main benefits of meditation is to reacquaint people with the pleasures of silence. This is particularly true for children growing up in the era of the smartphone. NewsFour spoke with Dr Michael Telford, Principal of the John Scottus School, Donnybrook where meditation is a practice encouraged among students.

“We have a programme, part of the overall ethos of the school, which emphasises the emotional and spiritual growth of our students. We have a pause before and after each class of the day, a silent period in the middle of the day for ten minutes and at the end of the day, a music period” Dr. Telford explains, “not necessarily music of the students own choice, quietening music.”

The John Scottus School was founded in 1986 and meditation has been part of the programme since day one. Dr Telford recounts that “[in] 1986, it was almost a hush-hush matter. ‘Medi-what?’ people would have asked. Now, it’s very much the norm and I think in the future, it will become standard practise in education.”

If it is now the norm, rather than a far eastern religious concept, maybe one way of looking at meditation is it’s part in the fine art of getting over yourself, and getting on with things.

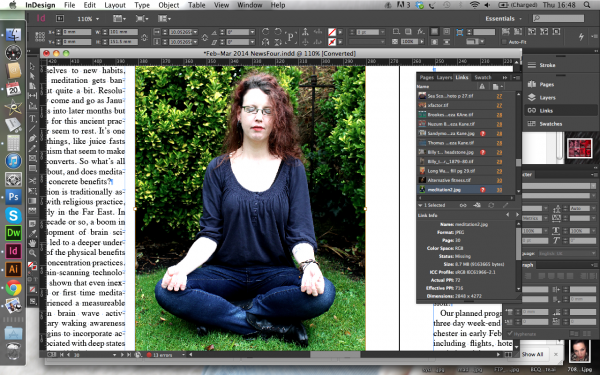

Meditation: a brief how-to guide

Broadly speaking, there are two basic approaches to meditation for the beginner: the exclusive or the inclusive. You have to ask yourself: do I want to focus on something as best I can, at the exclusion of all other objects of awareness or do I prefer to defocus and learn to observe the contents of my mind impartially?

Exclusive methods include focussing on the repetition of a word or phrase, or selecting a simple coloured shape to concentrate your attention on. Inclusive methods, which can be trickier for the beginner, involve watching the thoughts, the breath, and the body, as well as feeling your feelings but not trying to correct them, or interfere.

The next step is making an appointment with yourself to practice. Regularity is key. Just five minutes of gentle effort practice every day for about two weeks will get you started. It’s not so much about the exact same time every day so much as it is about making and keeping the appointment with yourself. Once the habit is engrained, a place of habitual reflection becomes established in the mind (however slight and insubstantial it may seem to begin with) and the deeper benefits of meditation will begin to reveal themselves.

The open secret of all meditation is the breath. A comfortable position, and smoothing, slowing and regularising the breathing are excellent controls for a beginner’s practice. If you’ve lost your focus, check your breathing. Emotional distractions always manifest in the behaviour of the breath and can be corrected by restoring smooth, relaxed inhalation and exhalation.

By Rúairí Conneely