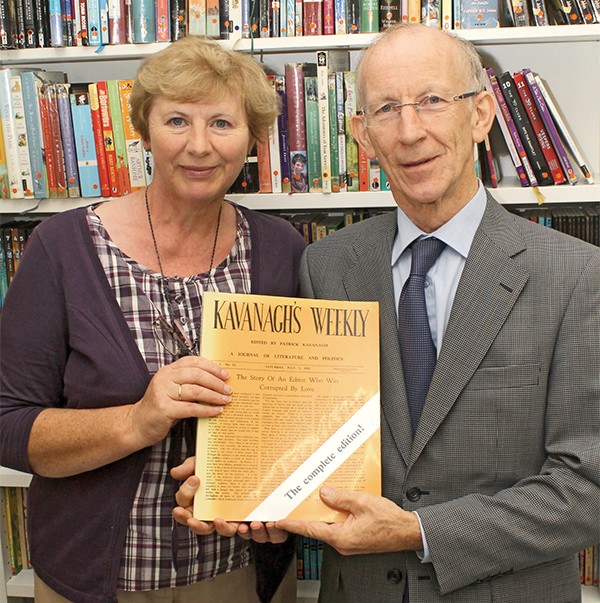

Pictured: Liz Turley of Pembroke Library and Kavanagh enthusiast Peter McDonnell.

1952 was the year that saw the publication of a journal of literature and politics by two brothers, Patrick and Peter Kavanagh.

Kavanagh’s Weekly lasted for just 13 issues. Kavanagh enthusiast Peter McDonnell presented a talk at Pembroke library on October 15th that painted a picture of the Ireland in which this short-lived publication gasped for air.

McDonnell grew up in the adjacent parish to the Kavanaghs, himself a native of county Monaghan, and was always interested in the life and works of the literary genius, fully immersing himself in the subject on his recent retirement from his position of Chief Medical Scientist, specialist in blood transfusion.

Although it had a short existence, the paper had a long-lasting effect on both brothers. Patrick was at the heart of The Weekly, as it was set up to give him a platform to express himself. He was more subtle than his brother and the consensus at the time was, “If Patrick is bad, Peter is worse.” Peter had a talent for getting people enraged.

Ireland of the 1950s was a bleak place in almost every way. It had the lowest living standards, highest emigration rates and the most intellectually stultifying society in Northern Europe. Peter, the less well-known of the two brothers, had just returned from America and observed that there was no shortage of material in Ireland to fill the paper. Issue 1 caused a sensation. “Being stupid and illiterate is the mark of respectability,” Peter wrote. “I picked off one government racket after another.”

The Weekly was published from 62 Pembroke Road, not far from where the library is now, and could be purchased for 6p. It was not an economically viable venture, but the motivation behind it was not financial. Bob Eason was approached but would not distribute it until his lawyer passed it as free of libel. As no such guarantee could be given, Peter distributed it himself.

The political commentary is uncannily relevant today. “Are our representatives doing anything other than siting in their embassies drinking whiskey and praying for the repose of the souls of the Christian Brothers who got them into the public service in the first place?” Of Radio Eireann’s licence fees he said, “We’re paying all that money to listen to the BBC.”

‘The story of an editor corrupted by love’ was the subtitle of the 13th and final issue. Patrick tried to explain why his paper would no longer be published. He justified his paper’s strong line against Ireland’s cosy relationship with those on the inside. “In Ireland, a man who is an individualist is starved into silence,” he said. “A writer is in need of an audience. Why there is no audience in Ireland for serious thinking is an interesting question.”

He praises Sean O’Casey in this vein, saying that he was right to go to England, as he would have been, like Joyce, “trampled in the gutters here.” He said the paper produced two kinds of readers: “Friends of a vague kind and enemies of a very precise kind.”

On July 5th 1952, both brothers signed off, and the remaining issues were burned in the fireplace of 62 Pembroke Road, giving the night skyline an orange glow. Patrick Kavanagh later said that The Weekly contained in its pages his best autobiography.

Peter McDonnell takes part in the annual series of events commemorating Kavanagh, of which this year’s highlight was on October 21st, Patrick’s birthday, with two presentations by McDonnell and a re-enactment of Kavanagh’s life and times by PJ Brady in Buswell’s Hotel.

For more information on talks in Pembroke library call Liz Turley on 01-6689575 or email pembrokelibrary@dublincity.ie

For more information on the Ballsbridge Historical Society, visit http://www.bdshistory.org

By Maria Shields O’Kelly