“Monto” is still a word that slips from the lips of Dubliners often, with an air of affectionate or roguish allusion. Monto was, of course, the infamous red-light district named for Montgomery Street (now Foley Street) and enclosed within the bounds of Talbot St and Sean McDermott St, and Lower Gardner St to Amien St.

The facts you always hear brought up in any article about Monto are that it was the basis for the Nighttown chapter of Ulysses, and that it was, at its peak, the largest red-light district in Europe: so having disposed of those clichés, we can move on to Hell.

Hell was the other great Dublin zone of iniquity, dominated by the presence of taverns, brothels and gambling houses, and sited, incongruously, in the lanes and alleys around Christchurch Cathedral. This area, encompassing Copper Hill, Fishamble St, Winetavern St and Cook St, was known by its dramatic nickname as far back as the 18th century, although little recognised today (maybe in part due to the influence of the Tourism Board and saintly auspices of the cathedral).

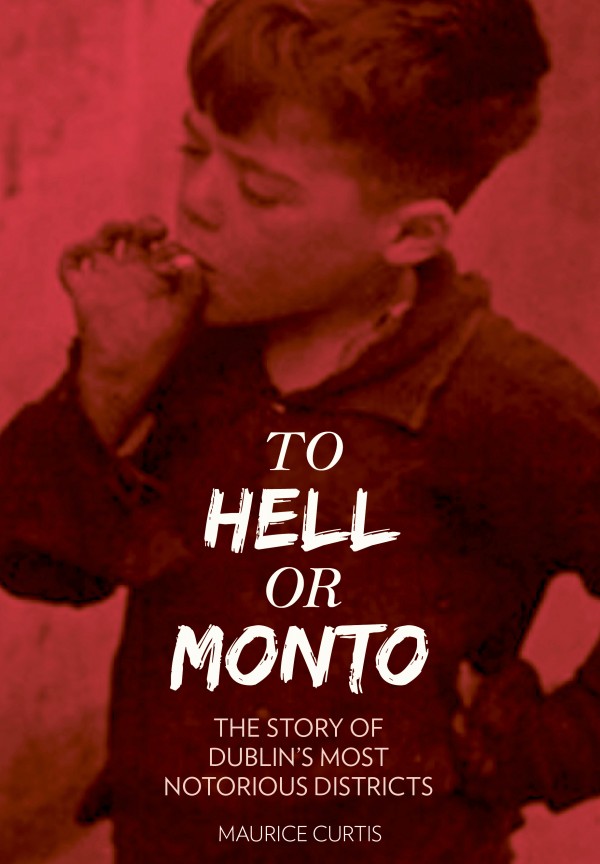

The full history of these infamous districts has been documented in a new book, To Hell or Monto: The Story of Dublin’s Most Notorious Districts, by Maurice Curtis. The book is a detailed and elaborate history of the times and places and, while diligently researched and engagingly written, isn’t afraid to have fun with its subject.

The chapter titles make full use of the bombastic implications of the two districts. Some stand-out examples are A Place called Hell: Tales from the Crypt and The Black Pig, the Black Dog and Hell. These chapter titles give a sense that the author is enjoying himself, which invites the reader to do the same, sidestepping the danger of a sense of a dull read.

Sidestepping morality in favour of a social analysis, Maurice explains, for example, that the reason for the founding of Hell was more to do with the poor quality of Dublin’s drinking water than the immorality of its inhabitants. The dangerously unclean water obliged people to consume beer, ale and whiskey instead, and created a demand for more taverns, as well as loosening inhibitions and enflaming the appetites.

He also draws a picture of the imagination of the times, contrasting Christchurch Cathedral with the tavern actually named Hell, which took up residence in the crypt beneath the cathedral itself, and was connected by association with the now-legendary Hellfire Club.

To Hell or Monto draws a straight line through time, from the 18th century, Hell’s heyday, through its decline with the demolition of the old system of lanes around Christchurch, and its replacement in the 19th century with Monto.

This straightforward approach allows the author to stop and divulge the details at length without losing the reader. The colourful (at a distance) gangs, brothels, madams and enforcers of yesteryear, and their interactions, are fleshed out with alacrity and an easy turn of phrase. Overall this is a good book about a little-appreciated part of Dublin’s history.

By Rúairí Conneely