By Eoin Meegan

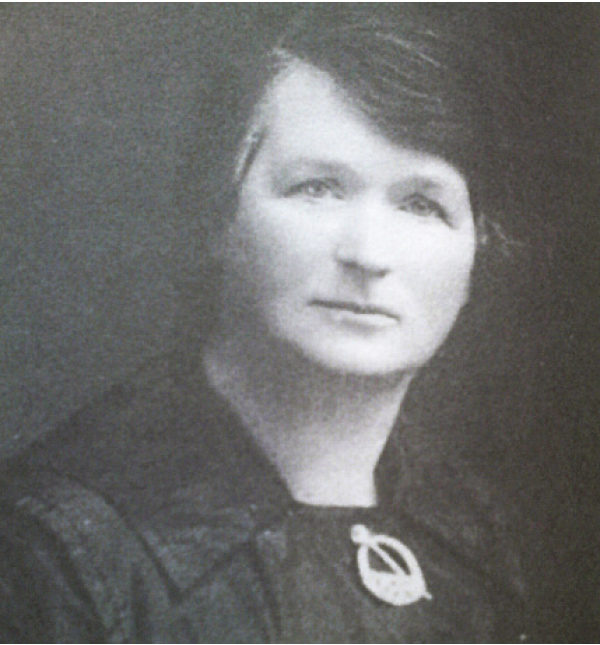

One of the lesser-known players in this country’s struggle for independence is one Molly Woods. A close friend of Michael Collins, Woods orchestrated the exchange of arms from her home in Donnybrook and provided a safe haven for volunteers, both throughout the War of Independence, and the Civil War that followed.

But Molly’s origins were far from the busy commerce of the metropolis. She was, in fact, born in Monasteraden, County Sligo, a beautiful spot a short drive from Ballaghaderreen in nearby County Roscommon. Her first encounter with insurrection had less to do with nationalism than with the pernicious landlord-tenant system of nineteenth century Ireland that saw many unjust evictions.

Molly recalls coming home from school one day and seeing a family sitting by the roadside in the rain surrounded by their meagre possessions. They had been evicted from their smallholding.

Showing a mixture of curiosity and naivety, she expressed astonishment that the family would not break the lock and go back in. When she was told that if they did they would be arrested and sent to prison, she inquired why their neighbours wouldn’t shelter them. If they did, they too could face eviction was the reply.

This experience made an indelible impression on the young Molly Flannery. Coming from a highly politicised family (she recalls at one time making flags at school), Molly was brought to meetings of the Land League with her parents from a young age where she heard John Dillon, William O’Brien and others speak.

The seeds of the Land League with its three-point demand: fair valuation, reduced rents, and security of tenure, would in time lead to the drive first for Home Rule, and then independence. Issues like personal freedom and women’s rights would inevitably become hitched to that wagon, and Molly would find herself at the heart of it all.

These meetings, along with her experience of local evictions, no doubt ignited that rebellious streak that was to define her later in adult life.

Losing her mother when she was only twelve meant Molly had to grow up quickly. Her maternal grandparents were both school teachers, a profession she herself would later pursue. Her grandfather, fluent in several languages, owned his own school and Molly was to follow in his footsteps.

She went to school in Ballaghaderreen, where she rose to be a pupil teacher. A vivacious and spirited character, once she turned down a good teaching post the local priest offered her because it came with one important proviso: she would be forbidden from seeing boys. Molly was having none of it.

She eventually became a private tutor to the children of P. J. Murray in Galway, a post she held for three years, leaving it to become a governess to the O’Farrell family. She travelled with them to Malta when Major General O’Farrell, Surgeon-General of the Royal Army Military Corps, was appointed Governor there. She loved her time in Malta, and undoubtedly would have remained there except that love intervened and 1902 saw her returning to Ireland to get married.

Showing an early talent for literature, Molly started writing poems and short stories when she was a child, but confessed she always struggled with her spelling. She became a member of the Irish Fireside Club, an early literary organisation whose aim was to spread education, and specifically kindness to animals.

Later she would join the Irish National Literary Society, and eventually was co-opted onto the council. Apparently, she showed some literary promise and had articles published in a variety of publications, but later decided not to pursue this career as her anti-war campaigning and other activities consumed all her time. Perhaps that is our loss.

It was through the Irish Fireside Club that she met her husband Andrew Woods, from Donnybrook. The couple started out as pen pals before she went to Malta and they had made the decision to marry even before they met in person. By all accounts it was a very happy marriage. Andrew was originally a supporter of John Redmond, the then leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, but came around in time to Molly’s more revolutionary mindset.

He was loved by all who knew him, known as one of those people who was kind to everyone, even those who might be considered his enemies. He had a great friendship with Michael Collins, and when he died in 1929 Eamonn De Valera helped to carry his coffin from their home in Morehampton Road to the Sacred Heart church in Donnybrook.

At first Andrew and Molly lived in Eglinton Terrace, and later in 131 Morehampton Road, known as St Enda’s, which became the hub of much revolutionary activity. There was always a window left open at the front and back of the house where volunteers who had escaped from prison or were on the run could come and go in a hurry.

There they would receive food, a change of clothes (on one occasion Molly even gave away Andrew’s best suit!) and weapons. Men like Sean Etchingham, Dick Mulcahy and Liam Mellows were regular visitors, and such to-ing and fro-ing naturally attracted the attention of the authorities.

Consequently St Enda’s had the distinction of being raided probably more times than any other house, sometimes twice in the same day. Molly would buy guns from the Free State soldiers and pass them on to the IRA. She also procured safe houses around the city at the behest of Michael Collins, including on Marlborough Road and Home Villas in Donnybrook, and St Mary’s Road, Ballsbridge.

On top of that she organised campaigns against conscription during the First World War, including a big meeting in Herbert Park, and was a member of Cumann na mBan, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, and also a Poor Law Guardian for the Dublin South Union. She made clothes for the children of local families who were experiencing hardship, and along with other women in the area organised parties for them and toys at Christmas. All this was done with no thought of remuneration.

Many great stories were told about the antics that took place at St Enda’s, and the clever ruses Molly came up with to frustrate the authorities. Like when the police once barged in when a gun was left on the table, Molly quickly covered it up and then told them her daughter had diphtheria and that it was highly contagious. The police made a very hasty retreat. At other times the womenfolk in the house hid weapons in their underwear.

Sometimes, when she knew she was being watched, Molly would go on a very long walk leading her pursuers on a wild goose chase. Molly was particularly fond of Liam Mellows. Liam was the son of an English army officer and a Wexford woman. He was born in Lancashire, but grew up mostly in Ireland and became a Sinn Féin TD in the first Dáil. Mellows played a leading part in the IRA contingent that occupied the Four Courts between April and June 1922 (which included Tony Woods a son of Molly and Andrew’s).

The siege famously ended when Free State forces bombarded the Four Courts; later Mellows was executed in Mountjoy. After the Treaty, which Molly opposed, former comrades became bitter enemies and this was a hard time for all concerned.

When hostilities ceased, Molly became involved in left-wing republican politics and was an active member of the Women’s Prisoners’ Defence League. In the 1930s she co-founded the Indian-Irish Independence League. having maintained an interest in Indian politics since her time in Malta. With the marriage of her daughter Ellen to a young Indian student, and her friendship with the suffragette Charlotte Despard, this interest was reignited in the 1920s and 30s.

She was a personal friend of both V. J. Patel and Subhas Chandra Bose. Patel, brother of Sardar Patel, became President of the Indian Legislative Assembly in 1925, while Bose believed in revolutionary overthrow of the empire and is said to have modelled himself after Michael Collins. Molly also met Gandhi and invited him to Dublin, but unfortunately it was not to be.

Recently, a laneway in Donnybrook, previously Belmont Court, has been renamed ‘Wood’s Way’ in her honour. It runs from Belmont Avenue to Mount Eden Road and is a fitting tribute to this woman who worked tirelessly to oppose injustice in whatever shape she found it.

Even if her star has faded somewhat with the passing of years, and those dark days have thankfully receded, people in Donnybrook still talk with fondness of Molly Flannery Woods, her eccentric manner and many brave deeds.