Peter McNamara

Have you been witness to a growing menace? A shock of hair that shocks your soul? Over the last year or so, a fringe movement has been resurrecting fashions of old. You might ask yourself, must humanity forever comb its past? Can we never make a clean cut?

Perhaps this reporter is overstating the case. Though they may not spell the death of any hope of progress or of linear time, one thing is for sure: the mullet is back. More surprisingly still, this once loved and later maligned hairstyle might be set to stay.

Before it even had a name, this long-in-the-back, short-in-the-front hairdo dominated the 1980s fashion scene. The bi-level. The Kentucky waterfall. The Missouri compromise. Hockey hair. No matter what they used to call it in the States, anyone who was anyone sported this trendy androgynous cut. That soon changed – somehow by the late 1990s the mullet was persona non grata, the shameful follicle foible of rednecks and oddballs, and any self-respecting person found wearing one should blush to their roots. Enter 2022, and this hairstyle once again finds itself adorning the heads – and necks – of the hippest of the hip.

Not only is the mullet making a comeback, it has actually been popular for centuries.

Without splitting hairs, it could be argued that, given our long history with the cut, the natural state of homo sapiens might be in wearing one: our evolved brains secure under an expanded cranium and neat-trimmed mullet. The short-long style has been sported by ancient warriors, pre-modern rebels and Enlightened leaders alike. From before the Stone Age, up to the time that Ziggy Stardust beamed down from Mars, the mullet has been a friend unto man and woman alike.

Ancient Roots

Literature’s first written record of this hairstyle comes from the ancient Greek poet Homer. In The Iliad, he described the Abantes, a group of spearmen, as wearing “their forelocks cropped, hair grown long at the backs.” But the term “mullet” wasn’t actually coined until 1994, thanks to the Beastie Boys’ song “Mullet Head.” The Oxford English Dictionary credits the hip-hop group as the first to use “mullet” to describe the high-low cut that’s long been described as “business up front and a party in the back.” The irony is, the cut was baptised after it was already dead – its 1980s reign had come to an end. The Beasties used it as a term of derision.

Although it doesn’t have quite the same archaeological provenance as hieroglyphs or dinosaur bones, mullet historians – yes, they do exist – believe there’s ample evidence to suggest that the hairstyle has actually been with mankind for centuries. According to Mental Floss, Neanderthals may have favoured it to keep hair out of their eyes and protect their necks from wind and rain. Ancient civilisations in Mesopotamia and Syria are believed to have utilised it. And this iconic do is plain to see on many Greek statues, dating right back to the 6th century BCE.

The mullet’s practical, adaptable shape has given it centuries-long staying power. It offered protection from the elements combined with improved visibility. According to Alan Henderson in his book Mullet Madness, warriors with the style were harder to grab during battle and could fight without the frustration of hair in their eyes. Added to that, helmets fit better with a short-on-top do. And at the tail end of everything, the longer locks at the back of the head likely helped early peoples keep their necks warm and dry.

In ancient Rome, the “Hun cut” was an early bi-level style sported by young wealthy bands of hooligans in the 6th century BC According to History.com they harassed the citizenry, and added insult to injury by styling themselves like Rome’s worst enemies: the fierce nomadic horsemen who terrorised the empire and helped hasten its fall. In his Secret History, the 6th-century Greek-Byzantine scholar Procopius wrote that “the hair on their heads they cut off in front back to the temples, leaving the part behind to hang down to a very great length.” For the old Byzantine, this mullet-like do was a “senseless fashion” – he can be thankful he wasn’t around for Miami Vice.

Cut to the Chase

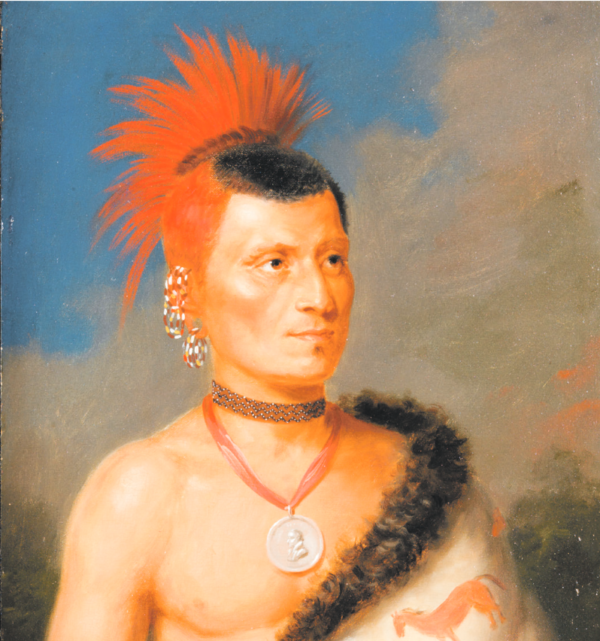

How did the mullet get so popular in the late 20th century? In the US, the style dates back to Native American tribes that often combined the look with a Mohawk. Although in the 16th century, Hittite warriors sported them, along with the Assyrians and the Egyptians, the Native Americans probably have the strongest claim to this do. They often wore it as a sign of spiritual strength, and the fact that the style was eventually appropriated by Western culture, and that colonial wigs – particularly that of George Washington’s – look a little mullet-esque, must come as a bitter irony. Riding on their “Manifest Destiny”, the New World newcomers stole a hairdo along with a homeland.

If the mullet-hawk was part of

the rebellion against the forced relocation of Native Americans, it contrasts starkly with events in the late 18th century, where President Benjamin Franklin adopted a ‘skullet’ – bald on top and long at the side – as a means of assimilating with the French to win their diplomatic support. According to Reader’s Digest, this founding father used his mullet-like stylings to help charm France into drastically increasing its financial and diplomatic support of America in the new nation’s earliest days. Despite his own cosmopolitan background, Franklin played the role of a rough-hewn bumpkin to win greater sympathy.

As far as America was concerned, conservatism would win out for much of the early 20th century, with men opting for short practical styles and women going to great lengths (no pun intended) to maintain an appearance of smooth, sleek professionalism. The idea of the mullet as a somewhat undesirable hairstyle would continue into the 1900s. In 1917 the term ‘mullet-head’ was used by American sociologists to indicate somebody of lesser intelligence or critical interest. And before that, in 1855’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Tom Sawyer refers to his Aunt and Uncle as ‘mullet-headed’ – and not as a term of affection.

As the 1960s and 1970s ushered in an air of anti-authoritarianism, some retrospective debate does exist as to whether David Bowie’s ‘Ziggy Stardust’ look or The Beatles collar-skimming locks could constitute mullets. Either way, no one can deny that they both altered perceptions of masculinity and femininity. According to hair historian (yes – they do exist) Janet Stephens, Bowie’s radical androgynous style combined what were traditionally seen as male (short) and female (long) elements. Not only did it “push the margins of hair and dress,” according to Stephens, it challenged ideas on identity and gender boundaries. His look would be endlessly reimagined by top rock bands and A-list actors for decades to come.

Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow

The 1980s was a time when the in-your-face statement style from the 70s became the norm. And the decade when the mullet transcended culture. Everyone from Metallica’s James Hetfield to Billy Ray Cyrus had one. Whether you were metal or country, yuppie or punk, jock or biker, the mullet was a mainstay. Patrick Swayze wore it in Dirty Dancing; as did Kiefer Sutherland in The Lost Boys. Though the style was seen predominantly on white men – with notable exceptions like Little Richard – a slew of female figures did rock the mullet; Cher, Jane Fonda, and Joan Jett among them.

What does Bono think when he looks back to the eighties? In those days, U2 could do no wrong, making classic albums like War and The Joshua Tree, and churning out hit after hit. As a guest on The Late Late Show, some years back, he did offer one qualification. “I have an erase button on the mullet hairdo.”

In the late 80s and early 90s, the trend began its decline. Despite notable exceptions – AC Slater in Saved by the Bell for one – the mullet was becoming one of the most divisive hairstyles of all time. As with so many cultural phenomena, it’s hard to pinpoint what caused this shift in opinion, but an emerging stereotype had taken shape. According to Dazed & Confused, a mullet denoted low-income families in backwater towns, redneck dudes in dive bars who clung to their beloved country music. A wounding blow came when the Beastie Boys mocked the cut on their 1994 track “Mullet Head,” a song that, despite the efforts of Tom Sawyer, the Oxford English Dictionarycredits with naming the fad. Suddenly, mullet-wearers were objects of ridicule and scorn, their locks outdated. The coup de grâce might have arrived in 1998, when for Lethal Weapon 4 Gibson lost his trademark cut. These were days shorn of hope.

No longer paraded by pop stars and TV hosts, no longer legitimised in the public eye, the hairdo quickly became taboo, a source of embarrassment for the same people who once proudly flicked their mullets into the wind.

It’s Growing on Me…

So how do we find ourselves in the midst of the neo-mullet? It probably stems from the recent obsession with throwback 80s nostalgia. In the last ten years of western culture, mullets have broadly remained tethered to 80s nostalgia. TV characters like Steve from Stranger Things have tipped their hats to the trend. And with mullet competitions also a thing, there’s a sense that it’s still one big joke. But the biggest culprit at play – and you might have already thought it could have done no further harm to humanity – might have actually been COVID-19.

The closing of hair salons during lockdown is the most likely reason for the mullet’s return. In September 2020, i-D called 2020 “the year of the mullet.” In an article for Vice Media, the mullet-wearing teenagers interviewed all described getting the haircut as a joke, with one stating, “there’s an irony to the mullet haircut. It’s this disgustingly gross haircut, which means it’s definitely worn in an ironic way.” With the world turned upside down, it seemed that good fashion sense has gone out the window. Speaking with Vice, Magda Ryczko, founder of the queer-owned barbershop Hairrari in Brooklyn, argued that mullets allow for a professional front facing look for Covid-19 era Zoom meetings, while maintaining a messier, more fun look at the rear, out of sight of the webcam.

According to Dazed & Confused, there were already signs of a comeback. In 2013, Rihanna sported a full-on mullet at the opening of New York Fashion Week, while Zendaya appeared on the red carpet at the 2016 Grammys with a more subtle take on the style. Everyone seems to have played their part in bringing the much-maligned mullet back to the future.

As a final word, given the modern style’s Native American origins, it seems appropriate that despite their return to general popularity, mullets remain an image of rebellion. In 2010, Iran banned the cut, hoping to stop the spread of what it called a “Western invasion.” In May 2021, North Korea’s leader banned both skinny jeans and mullets from usage, seemingly in fear that they might be a gateway to “decadent” western influences, while an Australian school also hit headlines for decrying the style as “untidy” and “non-conventional.” With people still pulling out their hair over this style, it seems the do has remained true to its roots!