By Geneva Pattison

It’s common knowledge that St. Patrick’s Church houses a beautiful stained glass window by none other than famed artist Harry Clarke.

However, another place you can view a piece of his less readily available work is at the Hugh Lane Gallery. Until 2020, the gallery will host a piece of fascinating work by the renowned illustrator and stained glass artist, the Gilhooley panel from his “Geneva Window”.

It was originally commissioned in 1925 by the new Irish Free State to be presented to the League of Nations in Switzerland but, due to the subject matter, it was ultimately fated to end up elsewhere.

Clarke took his inspiration from Irish literature and proposed to “work in panels for 15 Irish writers” showcasing scenes from their various works. A collection of archival papers on Clarke from the National Library of Ireland state that “WB Yeats was extremely enthusiastic about the window and made many suggestions”.

Clarke’s final selection of wordsmiths comprised of some of the most revered Irish writers of the early part of the 20th century; James Joyce, Padraig Pearse, Lady Gregory, Sean O’Casey, W.B Yeats, Seamus O’Kelly, Padraic Colum, George Fitzmaurice, Liam O’Flaherty, James Stephens, J.M Synge, Seamus O’Sullivan, Lennox Robinson and AE (George William Russell). Clarke spent most of the Summer of 1927 completing the window.

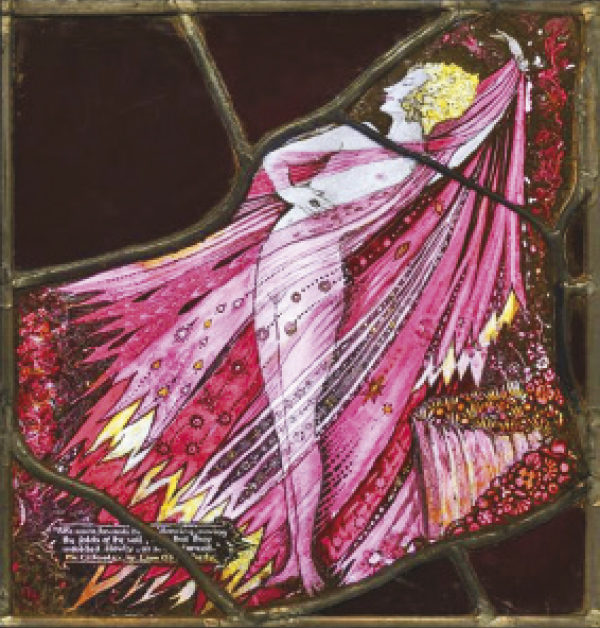

The single panel, on show in the Hugh Lane Gallery, was originally intended to be a part of the full window and was based on author Liam O’Flaherty’s novel Mr. Gilhooley.

However, the design was deemed too salacious by the Irish government, as it depicts a nude woman draped in a flowing transparent garment. Clarke used sultry pinks and reds for the material, which acts almost like a frame for the the woman’s dandelion yellow hair and alabaster complexion. Below the depiction, Clarke included a quote from the book; “She came towards him dancing, moving the folds of the veil so that they unfolded slowly as she danced”

There was a lot of indecision surrounding the palatability of Clarke’s stained glass creation, regarding whether the full window would be suitable for presentation to the league of nations for their International Labour Building in Geneva. It was criticised in the Catholic Bulletin by a reviewer, which added to its questionability as an acceptable piece of art.

Sadly, Harry Clarke died in 1931 and more than a year after his death the government had still not designated the window a permanent home. His wife and fellow artist Margaret Clarke was frustrated at this point with the disapproval from the conservative politicians. She took action and bought the window back from the government due to their lack of decisiveness with her late husband’s work.

In 1935 Thomas Bodkin, director of the National Museum of Ireland and friend to the Clarkes described the Geneva window as “ a major work of art, the most loveliest thing ever made by an irish man”.

The full window was kept in Ireland up until 1988, when Harry’s sons sold it to art collector Mitchell Wolfson. It is now housed The Wolfsonian museum at the University of Florida.

From Switzerland to Ailesbury Road

The Eve of St. Agnes is also on display in the Hugh Lane Gallery, featuring stained glass panels depicting scenes from Romantic poet John Keats’s work. It was commissioned by the owner of the Jacob’s Biscuit Factory Harold Jacob, to adorn his father George N. Jacob’s home, St. Michael’s on Ailesbury road.

The luxurious 21-roomed house was built in the style of an Italian Romanesque villa and needed something equally luxurious to echo Jacob’s taste. Harold is noted as saying to Clarke that he wanted “something out of the usual run of domestic stained glass”.

He had some ideas for the theme of the window, those being summer and winter or day and night, but went with Clarke’s more imaginative suggestion in the end. A thrilled Clarke wrote to Jacob right away stating, “I shall set to work on the Eve of St. Agnes and submit my first coloured draft for discussion”. For Clarke, this was a rare treat. His commissioned window designs mostly came from churches and institutions, with strict instructions in terms of design.

Well known Dublin furniture maker, James Hicks, designed the custom wooden slips to hold the Agnes window in the Ailesbury Road home. To have the creative freedom to interpret and bring to life a poetic work from 1820, during a very conservative period in Ireland’s history, must have been a magical experience.

The poem centres around a young woman named Madeline and her soon-to-be lover Porphyro. On the night before the feast of St. Agnes, Porphyro hides in her chambers watching her from afar as Madeline prepares for bed. He wakes Madeline by playing a lute as a storm rages outside against the window. As daylight will soon approach, they must flee into the cover of the storm, into the unknown, seeking desire and the divine from one another.

When it was released in 1820, Keats’s poem was considered improper due to the provocative subject matter. Again, we see Clarke exploring the controversial realm through his art. He creates sumptuously ornate visuals of Madeline’s bedroom by using jewel-toned colours. This reflects the abundant passion felt by the lovers and mirrors the decadent nature of the Keats poem.

This is in contrast to the panels depicting the land outside; there’s more of a monotonal quality to them. The harsh world, outside the impulsive love affair, is devoid of the colour of life. He builds on Keats’s descriptions of the lovers by depicting them gazing lovingly into each other’s eyes in the final panel as they escape.

The beauty and craftsmanship of the St. Agnes window was appreciated immediately and in August of 1924 Clarke was awarded the gold medal for Arts and Crafts at the Aonach Tailteann. After the death of George N. Jacob in 1944, St. Michael’s was sold and the window was moved to Carrikbryn, Harold Jacob’s Foxrock home.

Upon the death of Harold Jacob in 1949, his wife auctioned the St. Agnes window, which went to stained glass artist Richard King, who was once the manager of the Clarke stained glass studios. The St. Agnes window lay packed away for almost 30 years, until the curator of the Hugh Lane Gallery at the time, Ethna Waldron, acquired it for £20,000 from Mrs Alison King.

The legacy of Clarke can be felt across all of Dublin and Ireland. This master of the craft of stained glass brought dreamlike fantasies to life, in a time when day to day living rarely allowed for such whimsy to be indulged in.

Whether they depict imaginative secular subjects or those of a strictly religious nature, these pieces will stand the test of time as enduring works of art, long after we’re gone. He saw a world of possibility and infinite exploration through his designs and this sense of ingenuity will always ring true.

Much like the famous quote from George Bernard Shaw, “better keep yourself clean and bright, you are the window through which you must see the world”, Harry Clarke certainly opened people’s eyes to the mind’s potential through his creations.

To view the Geneva Window visit the Wolfsonian’s website: https//digital.wolfsonian.org

Details of Clarke’s career: https//www.nli.ie/pdfs/mss%20lists/clarkeh.pdf

Further information acquired from the book Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State, edited by Angela Griffith, Marguerite Helmers and Róisín Kennedy.