Pic: Home Instead

It was Florence McDonnell who answered Bernie Byrne’s call from Home Instead, for people to share their personal stories that were passed down by family members from 1916. “My father would sit the whole family down every Friday night and tell us all about the part he played in ‘the troubles’, as he called it.”

“Did you have to probe him or did he speak freely?” Byrne asks. “He told us everything; sure he was drunk,” was the reply that sent the room into hysterics. But despite the wit and good humor of the storyteller, a dark and palpable seriousness lurked amid the details.

McDonnell’s father, Christopher (Kit) Mullen was based in Boland’s Mill, Macken St, during the Rising. “He was a fierce Irishman and a real rebel.” Though it was the women who she considered to be the unsung heroes by her account: “Women played such a vital role and they are not mentioned enough. DeValera was against women taking part in the conflict. They just wanted to do their bit the same as the men. I think if I’d been alive then, I would have been in Cuman na mBan,” to which everyone in the room agreed with her. She is thinking back to her mother Kathleen who was only a young woman at the time, bringing her eldest sister to visit her father in Kilmainham Gaol where he was incarcerated in 1917. She told us, “There was a false well in the bottom of the high pram and she used to transport the guns in it. Sometimes the RIC man on duty would offer to mind the pram, not knowing it was full with ammunition. Then when she was visiting my father, he would take the baby to give her a kiss. That is when he would place the notes in her napkin, which my mother could then take on to headquarters.”

McDonnell reminisces about how difficult it must have been for her mother; a new bride, facing such hardship. “My father was taken to Belfast Gaol in 1918 and did not come home until 1920, banned for life from the six counties. There was no money coming into the house with her husband in prison and without the help of my uncles they could have perished. We got 10 shillings’ rent from the relieving officer, which wouldn’t even cover the 12-shilling rent. She told us stories of the Black and Tans raiding their house looking for guns and manhandling the women in the process. She often had to hide under the stairs with the children terrified for her life. She was a fierce rebel too. In later years I remember her calling people ‘turncoats’ if they didn’t stay loyal to republicanism.”

A recurring theme of the civil war years in Irish families was division. Brother against brother, with a barbarism equaling that of the Black and Tans. Kit’s only brother went with Cosgrave in this divide but unusually it did not create bad blood between them. It mainly served as a source to tease the republican brother. McDonnell tells us, “My uncle never spent a day in prison, had a steady income and received a pension. He would laugh at my father and say, ‘You’re on the wrong side.’ To which my father would say, ‘I’m fighting for my country: it’s nothing to do with money.” When Mullen was court marshaled, Noel Lemass, (brother of Sean) helped them and accompanied them to the trial. He later suffered a horrific death in the Dublin Mountains at the hands of fellow Irishmen, according to McDonnell. “They made my father Lord Mayor in the prison camp in Ballykinler and he always said that he was the only Lord Mayor who never lost his title.” This type of humour is a big part of McDonnell’s story. “My father was a sniper in the Hammond Lane foundry. He was caught up the mountains with gelignite and when he was asked what he was doing he said, ‘Going on a picnic.’”

McDonnell’s father Kit and those he fought alongside with, referred to themselves collectively as ‘The Boys’. “He would say ‘I was with The Boys’ when this or that happened.”

McDonnell’s first-hand testimony is invaluable. It is these personal stories that breathe life into the text of our history books. With the imminence of the centenary anniversary, the importance of saving these stories for future generations is urgent. McDonnell tells the story of this sacrifice because it is her story, too. Byrne asks her her opinion on what that sacrifice has meant for the last 100 years. “Unfortunately, I think it is still a very unjust society. When you look around and see homeless people and how older people are treated by the government, it makes me angry. I do hope everyone will decorate their houses with buntings and stuff to mark the occasion though.”

The one thing that sticks in her mind from this time is the love letters that her mother and father wrote in an attempt to keep the intimacy alive despite the distance between them. McDonnell and her siblings thought the idea of these ‘love letters’ was hilarious and they had a great laugh reading them. One line has stayed with her since she read it all those decades ago. Kathleen writes to Kit: “It breaks my heart when I hear the neighbor’s children calling for their father.” “I can still see that line.” McDonnell said. “I will never forget that line.”

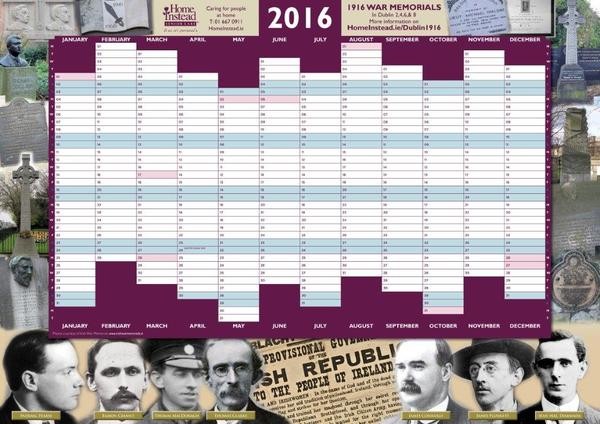

This event was part of Home Instead’s program of commemoration for 1916. They also have a special 1916 wall planner depicting portraits of the signatories and is a fitting tribute for the centenary which is available to clients and associates.

If you have a story to share, or would like to find out more about Home Instead, you can contact Bernie Byrne at bernie.byrne@hisc.ie or (01) 6670911.

By Maria Shields O’Kelly