Peter McNamara

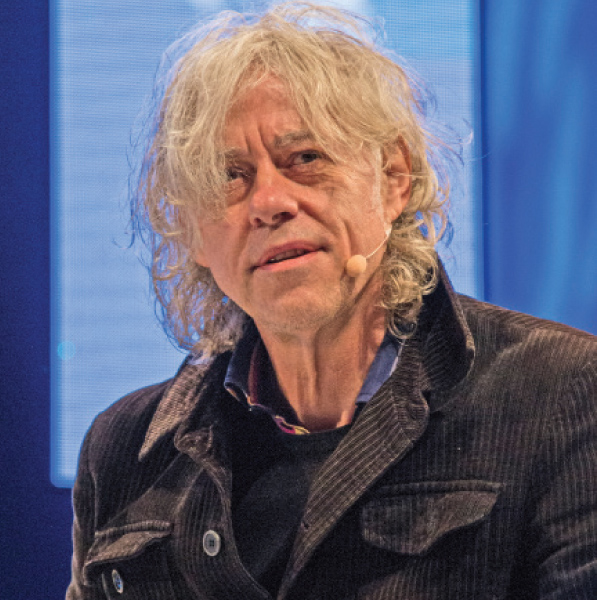

This summer will see the 35th anniversary of Live Aid, the greatest charity rock concert the world has ever seen. Masterminded by Dublin-born Bob Geldof, the event was organised in aid of Ethiopia, and the terrible famine it was suffering. Live Aid took place on Saturday July 13th 1985.

Two simultaneous concerts took place in the UK and America: 70,000 fans filled Wembley in England, and 100,000 came to J.F.K. Stadium in Philadelphia.

On top of that, with the help of all-new satellite technology, the concerts were broadcast live to a worldwide TV audience of over 1.9 billion people in 110 countries. The transmission even reached behind the Iron Curtain, which at that time still stood as a barrier to the West. All in all, the TV event lasted a whopping 16 hours.

Live Aid eventually raised $127 million in famine relief for African nations, and the publicity it generated encouraged Western nations to make available enough surplus grain to end the immediate hunger crisis in Africa.

It’s incredible to consider that a famine on the scale of Ethiopia in 1985 would never be allowed to unfold without intervention again, thanks in large part to the belligerent persistence of one man.

This has become such an iconic moment in rock history it is hard to imagine a world before Live Aid. These days, pop stars are a de facto branch of the international emergency services, offering a swift response to major natural disasters with charity singles and concerts – Lady Gaga’s “One World: Together at Home” virtual concert being the most recent such event in a long line.

Live Aid grew out of Band Aid, and the Christmas 1984 charity single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” In fact, after that single was released, the first spark of an idea to stage a subsequent charity concert to raise ever more funds for Ethiopia actually came from Boy George, the lead singer of Culture Club.

At the end of 1984, other performers from Band Aid joined him onstage for a sing-along of the super-group’s song. George was so overcome by the occasion he told Geldof that they should consider organising a benefit concert. Speaking to the UK music magazine Melody Maker at the beginning of January 1985, Geldof agreed.

“It’s a logical progression from the record,” he said, “but the point is you don’t just talk about it, you go ahead and do it!”

A “biblical famine” – an urgent response

Robert Geldof was born on October 5th 1951 in Dún Laoghaire, Ireland. When he was six, his mother Evelyn died of a cerebral haemorrhage, aged 41. He attended Blackrock College, where he was bullied for being a poor rugby player and for his middle name, Zenon.

After working in the UK and Canada as a slaughter-man, a road navvy, a pea canner, a music journalist, and a children’s television host, he returned to Ireland in 1975, and became lead singer of the Boomtown Rats.

In 1978, The Boomtown Rats had their first No. 1 single in the UK with “Rat Trap”, the first new-wave chart-topper in Britain. In 1979, they gained international attention with their second UK No. 1, “I Don’t Like Mondays”. In 1980, their single “Up All Night” was a huge hit in the U.S. and its video was played frequently on MTV.

The Christmas single that led to legendary concerts was inspired by a series of reports that Michael Buerk made for BBC television news programmes in 1984, which highlighted the famine in Ethiopia that was taking place at the time.

The BBC News crew were the first to document the famine, with Buerk’s report on October 23rd describing it as “a biblical famine in the 20th century” and “the closest thing to hell on Earth.” The reports shocked the UK, motivating the British people to inundate relief agencies, such as Save the Children, with donations.

Geldof and his then-partner, television presenter Paula Yates, watched the report broadcast on 23 October and were also deeply affected by it. A few days later, when Yates was presenting the weekly live music show The Tube, Geldof happened to speak to Midge Ure, lead singer of Ultravox (they had previously worked together for charity when they appeared at the 1981 benefit show The Secret Policeman’s Ball in London).

Geldof told Ure that he wanted to do something to alleviate the suffering in Ethiopia, and Ure immediately agreed to help. The pair soon came to the conclusion that the best option would be to make a charity record.

As Geldof recalled himself: “I rang Sting and he said, yeah, count me in. Then I got on to Simon Le Bon, and he immediately said tell me the date and Duran Duran will clear the diary. The same day I was passing by this antique shop and who is standing in there but Gary Kemp from Spandau Ballet… he said he was mad for it as well… suddenly it hit me. I thought, ‘Christ, we have got the real top boys here’, all the big names in pop are suddenly ready and willing to do this. I knew then that we were off, and I just decided to go for all the rest of the faces and started to ring everyone up, asking them to do it.”

Written by Geldof and Ure, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” was recorded in a single day on November 25th 1984 by Band Aid, a supergroup consisting of the biggest British and Irish musical acts at the time. Released on 3 December 1984, and aided by considerable publicity, it entered the UK Singles Chart at number one and stayed there for five weeks, becoming the Christmas number one of 1984. The record also became the fastest selling single in UK chart history, selling a million copies in the first week alone and passing three million sales on the last day of 1984.

The fundraising efforts got an additional boost when Wham! singer George Michael, who had appeared on the Band Aid single, donated all the royalties from his competing 1984 single “Last Christmas” to the Band Aid Trust. Wham! ended up selling over a million copies, and became the biggest-selling single never to reach number one in the UK.

The only man for the job

Once Boy George gave Geldof the idea for a charity concert, the Irishman set about making the seemingly impossible happen. In that Melody Maker interview from January 1985, Geldof’s vision was already taking shape.

“The show should be as big as is humanly possible,” he said. “There’s no point just 5,000 fans turning up at Wembley; we need to have Wembley linked with Madison Square Gardens, and the whole show to be televised worldwide. It would be great for Duran to play three or four numbers at Wembley, and then flick to Madison Square where Springsteen would be playing. While he’s on, the Wembley stage could be made ready for the next British act like the Thompsons or whoever. In that way, lots of acts could be featured and the television rights, tickets and so on could raise a phenomenal amount of money.”

Among the many, many people involved in organising Live Aid were Harvey Goldsmith, who was responsible for the Wembley Stadium concert, and Bill Graham, who put together the American leg. The concert grew in scope, as more acts were added on both sides of the Atlantic.

Tony Verna, inventor of instant replay, was able to secure John F. Kennedy Stadium through his friendship with the Mayor of Philadelphia. In this fashion, countless industry professionals volunteered their time and money, and innumerable favours were called in as people got into the spirit of Geldof’s vision.

Effectively organised in 12 weeks, the date and locations for the gigs were announced with only a month’s notice. Still, the newly-Christened “Global Jukebox” had little trouble selling out. After the monumental Band Aid single, and with so many stars adding their names to the bill, the event gained a momentum all of its own: professionals, broadcasters, celebrities, and punters alike knew that the concerts that were coming into shape would be something very special indeed.

Although there were a handful of notable absences (Michael Jackson and Bruce Springsteen being two), it’s difficult to name a major artist at that time who was not slated to play somewhere on the bill, either in the US or the UK. Everyone played for free, subject to terms they probably hadn’t suffered since the very early days of their careers.

Each act was given roughly 20 minutes to perform. There would be no sound check. In many cases, a band was denied the use of a lot of their own equipment, with many having to re-tune songs for stripped-down sets. Musicians shared and borrowed gear, and at the centre of the stage was a big red light that would come on when your time was up.

The stages were built. Fundraising centres were set up in countries all over the world to receive donations. As the corporate and television sponsorship deals were finalised, Geldof seemed to use every trick in the book to maximise funding.

Throughout preparations, the Dubliner pursued his vision with blunt force of will. To give one example, when negotiating an official drinks partner for the US event, he played Pepsi and Coke off against one-another, telling one company that their rival had offered him an extra $1 million in fees, when they’d done nothing of the sort. Sure, it was all for a good cause!

The “Jukebox” Comes Alive

Broadcaster Richard Skinner opened the historic concert with the words: “It’s twelve noon in London, seven AM in Philadelphia, and around the world it’s time for Live Aid.”

On a beautiful, sunny day, the concert began at Wembley Stadium with Status Quo, and their song “Rockin’ All Over the World”. After a performance from Paul Weller’s Style Council, Bob Geldof himself took to the stage to perform with the Boomtown Rats. Before kicking off their first number, he told the capacity crowd, “I’ve just realised this is the best day of my life.”

The Rats performed “Rat Trap” and “I Don’t Like Mondays”. During the latter, the band stopped mid-song, after the line “the lesson today is how to die”. In that moment Geldof raised a fist, to huge applause.

Queen’s twenty-one minute performance, which began at 6:41 pm, was voted the greatest live performance in the history of rock in a 2005 industry poll of more than 60 artists, journalists and music industry executives.

It’s hard to imagine that their blistering performance came as something of a surprise – at that time, Queen, the rock-and-roll mainstay of late-1970s, were somewhat out of fashion by the mid-80s. They took to the stage at Wembley in the early evening and blasted out a tailor-made medley of their greatest hits. Ten minutes in and the incomparable Freddie Mercury was in full flight; he got the crowd singing along in his trademark way, and his incredible sustained vocal at the end of their back-and-forth became known as “The Note Heard Round the World”. The band’s six-song set opened with a shortened version of “Bohemian Rhapsody” and closed with “We Are the Champions”.

It was Geldof who best summed up Queenʼs impact. “They were absolutely the best band of the day,” he remembered. “They played the best, had the best sound, used their time to the full. They understood the idea exactly, that it was a global jukebox. They just went and smashed one hit after another. It was the perfect stage for Freddie: the whole world. And he could leap about on stage doing We Are The Champions. How perfect could it get?”

After the gig, Mercury’s first words in his trailer were: “Thank God thatʼs over!” Adrenaline still pumping, he knocked back a large vodka to calm himself. The first person he met outside the door was a grinning Elton John. “Damn you!” he said to the triumphant Queen singer.

Other well-received performances on the day included those by U2 and David Bowie. Many musical journalists cite Live Aid as the moment that made stars of U2.

The Irish band used their allotted time in a less than orthodox way. They opened with a decent performance of “Sunday Bloody Sunday”, and went on to play a 14-minute rendition of “Bad”, during which Bono was mostly absent from the stage. The unexpected length of “Bad” limited the band to two songs; “Pride (In the Name of Love)”, their recent hit single, had to be dropped. Coming off stage, it was hard for the band to see their contribution to the day as anything but a failure, and a missed opportunity.

“We were really depressed,” said The Edge. “Bono felt it had been kind of clumsy and that generally the whole thing hadn’t lifted up.”

In the stadium, there seemed to have been an element of that. Guardian journalist Pete Paphides was in Wembley on the day. Watching U2’s performance, he was left feeling mostly confused. “From my vantage point on the pitch, near the halfway line, it was hard to tell what was going on. All we knew was that, during “Bad,” Bono was gone for an awfully long time, while the rest of his group acted as the musical equivalent of a plane circling the airspace near Heathrow awaiting permission to land.”

It was only the following day, when Paphides watched the TV tapes back, that he realised what seemed to have happened. Bono had jumped off-stage to pull a fan from the audience. He had picked her out and danced with her, planting a kiss on her cheek. It was a poetic moment, captured on television, it stood out beautifully from most of the other more predictable performances of the day.

Twenty years later, the Sun newspaper tracked down that fan and reported that Bono had saved her life.

“The crowd surged,” Kal Khalique claimed, “and I was suffocating – then I saw Bono.” In fact, Bono had long made a habit of pulling girls out of the audience and dancing with them. It seems very unlikely that Bono hadn’t planned to do the same thing at a show where this one powerful moment of personal interaction would be beamed live on television sets around the world.

Would there have been a fatality that day had Bono not miraculously seen her face from the stage? In the event, the world enjoyed a tender moment, and people finally began to see Bono as the messianic hero he wanted to be. Every available U2 album returned to the charts, and the band soon went on to write and record their seminal record, The Joshua Tree.

“Give me your f***ing money”

Throughout the concerts, viewers were urged to donate money to the Live Aid cause. Three hundred phone lines were manned by the BBC, so that members of the public could make donations using their credit cards. The phone number and an address that viewers could send cheques to were repeated every twenty minutes.

Nearly seven hours into the concert in London, Bob Geldof enquired how much money had been raised so far; he was told about £1.2 million. To put it lightly, the Dún Laoghaire native was said to be somewhat disappointed by the amount. Geldof marched to the BBC commentary position to push the audience into giving more.

The BBC presenter David Hepworth attempted to provide a postal address to which donations could be sent. Geldof knew that people wouldn’t go to the trouble of posting their money – they needed to be made to give on impulse, and for that reason the telephone line was a much more important means to win donations. As Hepworth read out yet another PO Box, Geldof interrupted him in mid-flow and shouted: “Fuck the address, let’s get the phone numbers.” Although the phrase “give us your fucking money” has passed into folklore, it was actually never uttered. Still, the Irishman knew how to push: after his outburst, donations increased to £300 per second.

The Philadelphia concert soon came online, and included reunions of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the original Black Sabbath with Ozzy Osbourne, the Beach Boys with Brian Wilson, and surviving members of Led Zeppelin. Phil Collins, who had performed in the United Kingdom earlier in the day, began his solo set with the quip, “I was in England this afternoon. Funny old world, innit?” to cheers from the Philadelphia crowd.

Duran Duran’s four-song set marked the final time the five original band members would publicly perform together until 2003. Their set saw a weak, off-key falsetto note hit by frontman Simon Le Bon during “A View to a Kill”. The error was trumpeted by numerous media outlets as “The Bum Note Heard Round the World”, in contrast to Freddie Mercury’s triumphant effort at Wembley. Le Bon later recalled that it was the most embarrassing moment of his career.

There were a few other small foul-ups. The transatlantic broadcast from Wembley Stadium failed during The Who’s performance of their opening song “My Generation”, immediately after Roger Daltrey sang “Why don’t you all fade…” – the last word “away” was ironically cut off when a blown fuse caused the Wembley stage TV feed to temporarily fail. Also, while performing “Let It Be” near the end of the show, the microphone mounted to Paul McCartney’s piano went dead for the first two minutes of the song.

At the conclusion of the Wembley performances, Bob Geldof was raised onto the shoulders of the Who’s guitarist Pete Townshend and Paul McCartney, for a rousing rendition of the Band Aid charity single.

The legacy of Live Aid

Geldof, the ever-unsatisfied idealist was heard to gruffly ask at the end of that monumental day: “Is that it?” That was it. History had been made, and the world has never seen anything like it before or since.

When the show was over, the after-parties began. And if the carry-on after the Band Aid recordings are anything to go by, they must have be raucous affairs indeed – following the recording of the charity single, rumour has it that Status Quo brought a little bag of something to the studio: musicians snorted, sniffed, and danced the night away.

Geldof and his team had originally thought the Live Aid concert might raise £5 million – the current tally stands at around £150 million raised as a direct result of the event. He mentioned during the concert that the Republic of Ireland gave the most donations per capita, despite being in the midst of a serious economic recession at the time.

What was disappointing was the lack of donations from big companies – banks, oil companies and other major players. It was left to the general public to donate, which they did. Music fans dug deep into their pockets, including one mystery woman from England who boosted the funds by personally pledging half a million pounds.

The impact of Live Aid on famine relief has been debated for years. One aid relief worker stated that following the publicity generated by the concert, “humanitarian concern is now at the centre of foreign policy” for western governments.

Geldof has said, “We took an issue that was nowhere on the political agenda and, through the lingua franca of the planet – which is not English but rock ‘n’ roll – we were able to address the intellectual absurdity and the moral repulsion of people dying of want in a world of surplus.”

Critics of the event point to the lack of control the Live Aid Trust had in where and how the relief money was spent. The organisers tried, without much success, to run aid efforts directly, channelling millions of pounds to NGOs in Ethiopia. Much of this ended up going to the unstable Ethiopian government of Mengistu Haile Mariam, and was reportedly spent on Soviet weapons.

On another point, BBC coverage co-host Andy Kershaw asked: in a concert for Africa, organised by someone who expressed concern for the continent, why didn’t Geldof “see fit to celebrate or dignify the place by including on the Live Aid bill a single African performer?”

Thin Lizzy keyboard player Darren Wharton also expressed regrets about the band not being asked to perform. “That was a tragic, tragic decision,” he said. “It could’ve been and it should’ve been the turning point for Phil. I mean he had a few problems at the time, if he would’ve been asked to play Live Aid, that would’ve been a goal for him to clean himself up to do that gig.” Lynott died less than five months after the concert, from complications associated with his drug and alcohol addictions.

All the same, such criticisms haven’t done much to tarnish Geldof’s reputation. He received many awards for his fund-raising work, including being invested by Elizabeth II as an honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1986. In actual fact, Geldof is entitled to use the post-nominal letters “KBE” but not to be styled “Sir”, as he is not a citizen of a Commonwealth realm. Nevertheless, the nickname “Sir Bob” has stuck like glue.

When faced with criticisms about the shortcomings of Live Aid, Sir Bob has always given a firm reply: “I’ll shake hands with the Devil on my left and on my right to get to the people we are meant to help.”